For a short time in 1912 Fes was the capital of French Morocco, until it occurred to Maréchal Lyautey that the oyster-grey city, far inland below the heights of the Middle Atlas, was not a very secure location for an imperial capital. Apart from anything else, naval access was distinctly limited. The march to the nearest port was long and dangerous. In 1912, after two sieges of Fes in quick succession, his attention switched quickly to Rabat on the coast, 130 miles and a week’s ride away through the Marmora forest. Rabat was eventually declared the new capital of Morocco, after a long bout of slightly mysterious arm-wrestling with Paris. It was – for the purposes of colonial government – a much more sensible choice.

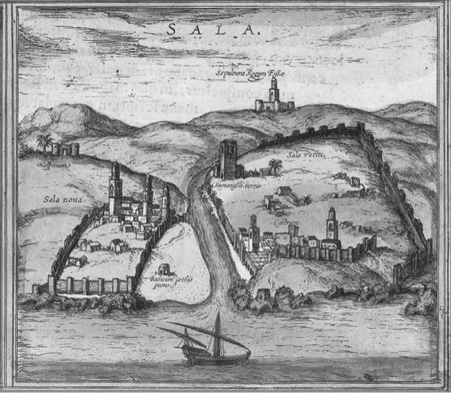

Engraved view of Rabat by Braun and Hogenbergt, 1572.

Rabat was an ‘Imperial City’, which is to say that it was a habitual stopping place for the sultans on their royal progresses around their possessions, and that it boasted a royal palace. Indeed it boasted two, the great enclosure of the Mechouar with which we are familiar today, and the Qubaybat, the ‘Little Domes’, as the summer palace down by the sea was known, lost as it now is beneath the oddly Gormenghastian remains of French military and medical buildings. Like Salé across the river, it was a way-station on the only secure north-south route between Morocco’s two chief capitals, Fes and Marrakech, and thus strategically important in its own right. Lyautey described it as lying ‘at the intersection of the three major axes of Morocco, one towards Taza, one towards Marrakech, and the third one along the coast …’ and in the light of this strategic centrality it is surprising how small a part Rabat had actually played in Moroccan history in the preceding millennium.

But it had another feature too, which made it extraordinarily suitable for development as a colonial capital, a feature that was the product of Rabat’s strange, episodic, history. The little city on the southern tip of the Bouregreg estuary occupied only a tiny portion of the walled area that Sultan Yacoub al-Mansour had enclosed in the twelfth century for his new capital: al-Mansour’s city walls still stood tall, but they enclosed smallholdings and rough pasture and a good deal, too, of waste land between the marshy edge of the river and the Mechouar. Like Rome in the early Renaissance, the city had shrunk to a tiny fragment of what it had been – or, in the case of Rabat, had been imagined as becoming – and much of it lay empty, protected by high walls, open and inviting to the French architect of empire.

The rest of this article is only available to subscribers.

Access our entire archive of 350+ articles from the world's leading writers on Islam.

Only £3.30/month, cancel anytime.

Already subscribed? Log in here.

Not convinced? Read this: why should I subscribe to Critical Muslim?