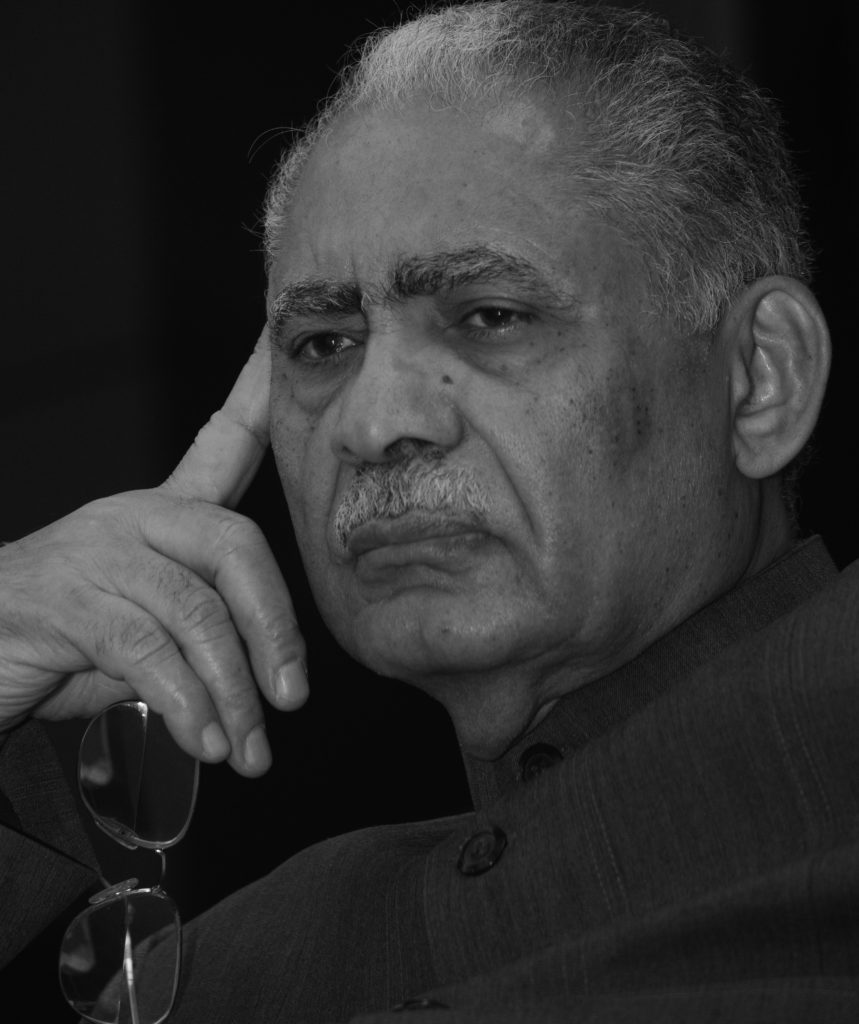

On 18 August 2021, the world shined a little less bright with the loss of AbdulHamid AbuSulayman. Islam teaches us to grapple with the life-long challenge of improving ourselves as individuals while also seeking to better our communities and societies. AbdulHamid personified the true spirit of Islam through his thoughts and actions. He leaves a profound intellectual and institutional legacy designed to improve and reform Muslim societies.

AbdulHamid was born in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in 1936. He followed most of his contemporaries to Egypt to study political science at the University of Cairo. After finishing his studies in Cairo, he moved to the US, where as a student, he was involved in establishing the Muslim Students’ Association of the United States and Canada (MSA) and the Association of Muslim Social Scientists (AMSS). He obtained his doctorate in international relations in 1973 from the University of Pennsylvania. A few years later, he returned to Saudi Arabia to teach at King Saud University in Riyadh, and become the Chair of the Department of Political Science from 1982 to 1984.

I first met AbdulHamid in the mid-1970s, in the heyday of what was then seen as a period of ‘Islamic Revival’. Intellectuals, thinkers, academics, activists, modern, and traditional scholars crossed paths and often engaged in furious debates. But we were far from united in our thinking. In fact, the ummah might have been at its most divided, the juxtaposition of ideas was at times overwhelming, and the only unity to be found was in our own individual positions which were inevitably seen as the right cure for our collective sickness. We debated what was to be done amidst the backdrop of turbulence from the siege of Mecca, Soviet encroachment in Afghanistan, the burning of al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Arab-Israeli wars. Many of us came from fledgling nations and hoped to survive past infancy and develop into strong states with new ideas and innovations. Some of us spoke of postcolonial matters, some wanted to embrace modernity, some feared secular democracy, while others were concerned about civilisational interregnum and authoritarianism. There were calls for jihad, reform, and even revolution. A few audacious individuals considered the future. By then, AbdulHamid had become the Secretary General of The World Assembly of Muslim Youth (WAMY), based in Riyadh, and I was with Malaysia’s Muslim Youth Movement (ABIM). We had a common friend: the noted Palestinian-American philosopher and scholar of Islam, Ismail al-Faruqi, who was a frequent visitor to Malaysia. Al-Faruqi was a popular speaker and debated with many of the top scholars in Malaysia. Al-Faruqi introduced me to AbdulHamid; and I invited him to come and speak in Kuala Lumpur. My first impression was of an exceptionally gentle and polite person, who displayed unassuming confidence. Eventually, I was invited to join WAMY as a representative of Asia and the Pacific. We became close friends. The conversations al-Faruqi led would bring AbdulHamid, myself, and a brilliant assembly of expat scholars from across the Muslim world together. Our rather intense discussions would lead to the establishment of the International Institute of Islam Thought (IIIT).

AbdulHamid was a brilliant scholar and consummate teacher. Great scholars tend to be great teachers who hold high standards for their students; and do not hesitate to correct them when necessary. His natural aptitude towards education began with the way he used to correct my pronunciation of his name. The Malay language preconditions us towards short cuts and abbreviations. So, when I would introduce him as AbuSulayman, each letter given the same stress, he would object with an aside, ‘Brother! Sulaymaan’. In Malay, we would add an extra ‘a’ to his name, to extend the sound and ensure this faux pas would be avoided; and an extra ‘a’ would be added to my grandson’s name too, so that I would not have to be met with continual reprimand for my impropriety. The details, where it is said the devils tend to hide, mattered to AbdulHamid. He was meticulous in everything he did, paying serious attention to every element.

His main concern was the reform of Muslim society. He wanted to direct our attention to the roots of the problems of the ummah; and the reforms he sought were lived reforms, beyond platitudes and empty promises, ready-made solutions and quick-fixes. His first major work is Towards an Islamic Theory of International Relations (1973), which was the result of his doctoral work at the University of Pennsylvania. But it was his second book, The Crisis of the Muslim Mind (1986), that turned into a project and propelled his life’s work.

AbdulHamid saw the malaise of the ummah both in terms of a deficit of education and an encultured limitation on the mind. He described the later as a breaking from the Qur’anic Worldview, which he would address more fully in his later 2011 work aptly titled The Qur’anic Worldview: A Springboard for Cultural Reform. For AbdulHamid, the problem of the Muslim mind arose out of an unconsidered adoption, writ large, of Bedouin Arab culture. He was influenced by ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), who noted the variety of qualities that enabled the Bedouins to survive and thrive in their environment; but when immobilised and removed from such existential threats, these same qualities would lead to a decline of civilisation that inculcated them. AbdulHamid referred to this as the ‘Desert Worldview’, a mentality that allowed for an exclusivism and chauvinism and gave rise to racist and dictatorial tendencies that thrived in Arab tribal culture, and became dominant within early Muslim civilisation. As this trend rose to prominence, AbdulHamid wrote, ‘the Muslim community fell prey, increasingly, to lethargy, stagnation, passivity, superstition, and sophistry. As a consequence, the foundation of knowledge and strength upon which this community had originally been founded began to crumble, while the guiding light of reflection, investigation, creativity, and conscious stewardship steadily died out’.

AbdulHamid traces the roots of this decline to an unreflective embrace of the Prophet’s language. The Prophet had to sometimes resort to a discourse of warning, a cultural staple of the desert worldview, ‘to bring them out of their primitive social and cultural state into an understanding of the basic starting points for creating a global civilisation based on the Qur’an and its teachings.’ Disregarding the changing context of the world, the ummah failed to move forward to something more universal and so the desert worldview superseded the Qur’anic one.

There is an echo here of the criticism of the late Egyptian scholar, Muhammad al-Ghazali (1917–1998), who criticised the fiqh mentality adopted by many Muslim thinkers. Fiqh mentality reduces the world down to the convenient simplicity of halal and haram, right and wrong, particularly in terms of judicial judgement. Al-Ghazali called for a rectification of the heart, where spiritual nourishment and an exploration of ethical values were a greater service to the Sharia and the ummah than the rigid dogma of the fiqh mentality. This mentality reflects AbdulHamid’s desert worldview, giving rise to an empty traditionalism where customs are repeated while their relevance and meaning are lost. Life is reduced to going through a set of motions, and spiritual purpose, as well as solidarity and empathy with our neighbours, is forgotten. This uncritical approach to Islam was the death of faith for AbdulHamid. The resulting fiqh mentality ossifies the lived faith of Islam. Islam become a religion of blind followers, often misguided, and detached from their relationship to Allah. A believer’s critical engagement with the Word and the world evaporates. This is precisely the crisis of the Muslim mind that prevents the ummah from realising its civilisational potential.

Ibn Khaldun’s analysis traces the way this brought about the decline of the classical Islamic empire. Ibn Khaldun commended the Bedouin for their strong level of asabiyyah, the potential for social cohesion, a product of efforts to survive the harsh and unforgiving climate of the desert. While it served well for the expansion and conquest that transformed the early Muslim community into a world civilisation, ultimately, no longer living in such harsh conditions, it turned asabiyyah from a unifying sensibility into a reductive and destructive nationalism – with higher value absent, ransacked with racist undertones, and entrenched within the exclusivist and dictatorial might of the desert worldview. Ibn Khaldun hoped that the asabiyyah could again be revived but as a tool for solidarity and unity. AbdulHamid saw the revival by going forward to the Qur’anic worldview.

AbdulHamid believed that the contemporary neo-conservativism and racist tribalism devoid of critical thought is not some preordained fate of the ummah. Indeed, history provides us with examples of those who broke the chains of the desert worldview and sought reform and return to the Qur’anic worldview. One such figure was the great Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi (1137–1193), who became the first Sultan of Egypt and Syria. He has been somewhat mythologised in an unfair cast of romantic nostalgia by Muslims, but aside from his military prowess as the hero of Jerusalem, AbdulHamid cited Salah al-Din as an example of one whose work to establish robust and sustainable systems of education in the Holy Land was shaped by the Qur’anic worldview. I would also add to this example Salah al-Din’s entire administration of Jerusalem. He possessed a natural talent at networking for peace. Without a doubt, Salah al-Din was an exceptional military commander and strategist, but he surpassed himself in his mastery as a diplomat and in maintaining peace in one of the most diverse regions of the world, Palestine – particularly amongst Muslims, Christians, and Jews despite the macroaggressions occurring outside the city walls. His effective leadership and adept approach to events unfolding before him allowed him to maintain trade in Palestine and oversee peace amongst all the diverse communities of the Holy Land. He also nurtured good ties with the Byzantine Orthodox Christians as he held off Crusaders from the West. Moreover, he instilled an awareness and understanding in society and its institutions to ignite a spirit of reform and learning. His example of good governance was forged in a delicate balancing act that saw the construction of new mosques, improvements to the economic situation, as well as physical infrastructure of the region, and social reforms achieved through advancing the state of education.

Salah al-Din’s spirit and example informed many of our debates as we endeavoured to build IIIT throughout the early 1980s. To confront the crisis of the Muslim mind, we set out to invigorate an intellectual revival of academic thinking on the basis of AbdulHamid’s Qur’anic worldview. This took us through projects of de-westernisation of knowledge to Islamisation of knowledge, and finally nowadays, to the Integration of Knowledge as we set about resisting secularisation and navigating decolonisation of culture and institutions. We would stand against the taqlid (conformity to the teaching of others) of misguided fanatics as well as talfiq, the imitation found in grafting Western solutions onto our problems. We needed a new way that brought us back to Islamic values and the Qur’an. We need to tear down the desert worldview of dichotomising good and bad so that we could attain a more sophisticated, moral ethics capable of engaging with the complex, chaotic, and contradictory issues of our postnormal times. I think I was the only one who was not a scholar in the group, but we were not simply armchair philosophers or intellectuals confined to the ivory tower. We worked to become agents of the change we desired. And this did not stop AbdulHamid and myself from having our great chicken-or-the-egg debate on how to bring about the social reform we sought.

For me, good governance was the key to curing a society’s ills. AbdualHamid fervently disagreed. For him, it was a robust education that must come first in order to heal our civilisation. He argued against any of us getting involved in the nasty enterprise of politics. In contrast, I would retort by saying that without good government there is no one to support our new ideas and efforts. Far too many oppressive regimes have stymied the flourishment of the people’s minds and their educational systems. Yet, AbdulHamid persisted, without a good education, you cannot create the ruling class with the capability of empowering educational progress. So, in the end, no resolution could be reached on this debate. But Salah al-Din provided the example whereby we could both have what we needed. As the sun began to set on the 1980s, we would be presented with our opportunity to actualise all that we had been arguing back and forth on for at least a decade: in the form of a university.

I went into politics in the 1980s, much to the chagrin of AbdulHamid. In 1986, when the term of the first president of the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), former Prime Minister Hussein Onn came to an end, I was Minister of Education and was named as his successor. The university had been established but there was much work to be done in turning it into the intellectual centre we had envisioned. Being a minister and a member of parliament, I needed a trusted team to help with advancing IIUM, to live up to the name we had given it, and I had just the person in mind. And I had another point to make in the recurring debate between AbdulHamid and I. As someone in politics who was a minister, I was in a position to take our intellectual and reform agenda forward.

I still remember being in the car, operating one of the bulky, early model, mobile phones and calling AbdulHamid in Washington, DC. Would he accept the position of the new Rector of IIUM? As I went about explaining the situation and the opportunity, he was shocked. He had thought I wanted him to be a visiting scholar with an honorary and temporary post. But, I said, we have had too many guest lectures, it is time that we did something substantial. We have an incredible opportunity with me as the minister and a relatively new university. We can transform it into a bastion of reformist thoughts and ideas. AbdulHamid paused for a thought. ‘When do you want me to start? Tomorrow?’, he asked. I told him to take at least a week, perhaps consult his wife. But the week had begun and he agreed without hesitation, and this was before we had gotten into the negotiations of salary or the logistics of moving his family half way around the world. This has always stood as a wonderful illustration of the man AbdulHamid AbuSulayman was.

When AbdulHamid arrived in Malaysia, no time for adjustment, even to the tremendous jetlag he must have felt, was needed. Few have possessed the level of commitment and dedication he had for the university. In public he was the perfect example of cordiality. But in private, I was in for one of the greatest battles of my over forty years in public service! There was continuous warfare between us, his passion would have it no other way. ‘Brother’, he would say, ‘this is the university, this is where civilisation is made!’ As a minister, I had to abide by the budget and had to act fairly to the other universities. But AbdulHamid would ask me if I wanted ‘some run of the mill university for the sake of political expediency so that you can show the world what a great product we have, or do you want the university, that services its conceptual and institutional purposes to society?’ This was not to be a mere centre of excellence, but a civilisational endeavour that saw to the betterment of society, just as we had discussed during all those IIIT meetings.

Eventually, AbdulHamid’s meticulous attention to detail saw a major transformation of IIUM. I can confidently say that without AbdulHamid, IIUM would not be the world recognised institution it is today. From the architecture of the buildings to the structure of the Kulliyyah (university departments), he proved himself not only a brilliant academic but also an effective manager as well as a visionary leader. I had let loose a workaholic who would not rest until the good work was done. His wife Faekah even joked that AbdulHamid had two wives, her and the university. He built a new campus for IIUM, transforming a hill in Gombak, Selangor, into a mini city, a sanctuary for thinkers, learners, and those who sought after truth. He brought world class graduates to the university from abroad; and they returned home to take on leading positions in Bosnia, China, Albania, Indonesia, the Philippines, and throughout Africa. And his efforts also lead to the beautiful medical campus in Kuantan. Throughout the 1990s, we had built something truly remarkable.

As someone who has always lived in Malaysia, AbdulHamid had expanded my sense of what home means. His home was the world and his family was the ummah. And while born in Saudi Arabia, he left his mark both in the United States through his university education and work with IIIT and also in Malaysia which will serve future generations of Malaysian and international students at IIUM. He made a faraway land, of infinite diversity and languages he did not speak, into a home by the strictest definition of the term and built bonds with people stronger than those to our own blood-bound family.

Yet, as Ibn Khaldun says, each cycle of history must give way to the next. One of my greatest heartbreaks in life came in the form of a lesson that when you dedicate your life to justice and doing what is right, those who would have it otherwise do not only take you down, they also go after friends and family. But in the hardest of times, we also see the reality of those bonds of friendship. Following my sacking from government in 1998, my home at the time had become a public square of sorts, filled with outraged citizens calling for an end to the toxic politics of Malaysia, and for long overdue (even back then) reforms. Despite being apolitical, AbdulHamid and Faekah would be there every day, giving their support even though they could not understand all that was being said around them. AbdulHamid was a loyal friend.

One day, the cries of the public were interrupted by the Royal Police, who burst into my house, arrested me and took me away, in front of a huge gathering of protesters, to prison. While in solitary confinement, I learned that AbdulHamid had also been removed as Rector of IIUM, and would be leaving Malaysia. I was overwhelmed with grief. AbdulHamid and his family had made Malaysia their home, his children had grown up in the land I call my home. So, with the best handwriting I could muster (which is not particularly good in the most ideal circumstances), with the materials made available to me in my prison cell, I penned something I had intended as an apology that played out more as a call to action. In the end, it was a reassurance to a friend that I would not go quietly into the dark and history may remember it as the most unusual Eid address I have yet given. For Ibn Khaldun also said that cycles of history repeat themselves, after the fall and collapse, a new cycle begins and there is an opportunity for reform and change that could lead a civilisation into a new epoch.

The only things available to me in solitary confinement was my reflections and so I took stock of the lessons my great teacher, friend, and brother, AbdulHamid, had taught me. The reform agenda would not fail, there were too many great minds creating too much knowledge and wisdom for it to all to be for nought. Those who take comfort in ignorance and thrive on the withholding of justice will have their comeuppance. Despotic dictators would burn out and be overthrown. Reform will always win, we had laid the foundations, so we would just have to bide our time. There was always hope; and IIUM was left in good hands while we were away. The letter concluded on the sorrowful note. ‘What sort of a Muslim farewell was this!’. No dinner, no presents! Something far too familiar in the midst of the ongoing pandemic. All I can give now is all I could give then. Al qalb bil qalb! Heart to heart.

Following the historic 2018 Fourteenth General Election, the flame of hope was once again reignited in Malaysia; and I was happy to bring AbdulHamid back to a global home one more time. While in Malaysia, he endowed an international student fund in his name that, insha’Allah, will continue to secure the education of future students for a long time to come.

AbdulHamid taught us that education was not just about learning, but also about developing. He stood against the rigid dichotomy between the secular and the religious and challenged us to revive the Qur’anic worldview by doing away with the petty cultural differences that do little more than divide us. As a guiding force, education involves going out to the people, improving their insight and foresight, and working to transform their social and economic conditions. Educated people, AbdulHamid had argued, were agents of change, they cultivate the flame of knowledge so that it may burn so bright and not diminish, even after we perish. As I say yet another farewell to AbdulHamid AbuSulayman, I recall the words of the French philosopher and resistance fighter, Roger Garaudy. ‘To be faithful to our ancestors is not to preserve the ashes of their fire but to transmit its flame’. And the flame of AbdulHamid will burn on in the thoughts and actions of those he touched through his work with IIIT; and the hundreds of students at IIUM he inspired and sent off to different corners of the world.

Brother AbdulHamid, you have left the ummah and our civilisation in good hands.