In her work, Amina Atiq, a Yemeni–Scouse performance artist, explores the conflict and beauty of her dual identity, taking us on a journey to her heartland, Yemen, and her homeland, Liverpool. This is an extract from her first one-woman show, titled ‘Broken Biscuits’ – a reference to her grandmother’s 1970s Liverpool corner shop.

I held Granma’s hands in mine like a vessel of the past that feels strange goodbyes passed the Northern valleys and greeted the Southern blue waters

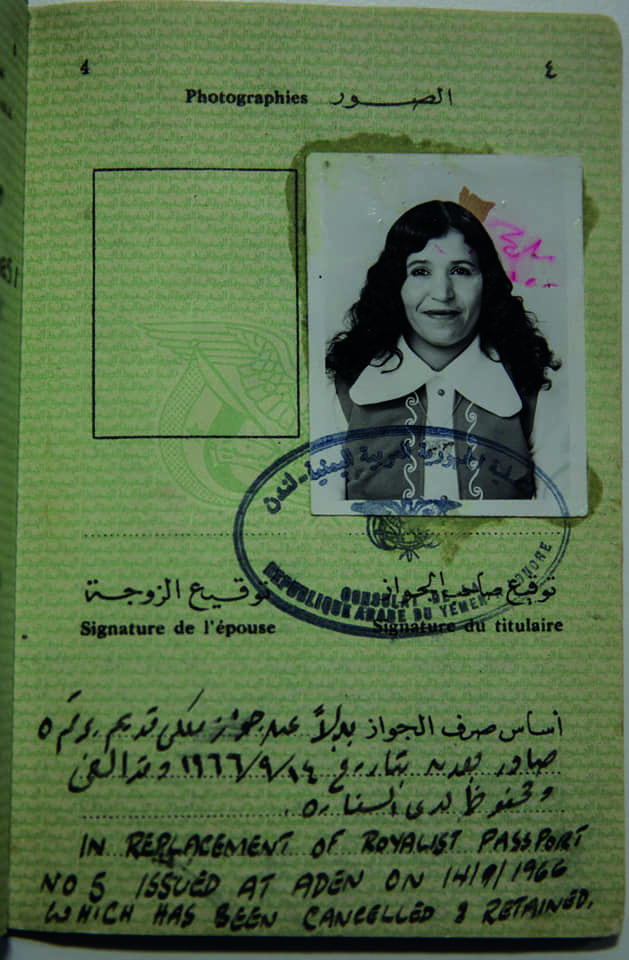

In the replacement of the royalist passport, number five issued at Aden on 14th September 1966, which has been cancelled and retained.

Unlocking the fishermen’s Red Sea – colony crown reeked of death

the British empire’s protection in the Aden region was an illusion.

buried in my foreign blood –

tea bags for mocha beans. Grenade bombs and rifles overthrown in the tribesmen hands.

Martyrs will meet life and justice will dance on the heads of snakes

ambushed in rocks and the mountains grew eyes. They don’t like invaders who overstayed the hospitability of the three-day rule –

it turned cold quickly, over the Mediterranean.

In bloodshed, English toddlers left the land with Arabic ringing in their ears, in their first language and memories of an invasion they did not ask for, strip searching Yemeni fathers with their hands in the air. The intense rage of the Yemeni people overthrowing them.

They lost the occupation in bitterness. An occupier never admits and history books written by the victors who dream of victory that deny its failure, walk home with their shoulder’s slouches like a turtle’s back.

I’m a dark horse

beating down the door somewhere childhood

escaped the streets etching three syllables of my name beneath the old city of Bab Al- Yemen

a woman dressed in black found me shackled to the gates, it was my mother, chewing on her ruby passport

it’s time to leave.

Yemeni families made their first appearances in Britain in groups, in the hands of a revolution leaving a civil war to unravel. They came with briefcases of gold, milk and honey.

We emptied our homes

unpacked our belongings

but some things we tucked under

our arms until someone else wore it better

because women like me buried home in our bellies

like our father’s names,

they call him Mo for short.

Or Danny from the Paki shop

Who is told to: only speak English here.

We had moved around twice, left the corner shop and moved to a council house not too far. No-one moves too far, we were hurdled up, promising to leave no-one behind. Outside this home, strangers lurk in the shadows and when they did not like the way you speak, they would look at you differently. My mum kept us close. We kept each-other close.

We lived on top of a newsagent; grandad’s corner shop but we never met him – we used the deserted shop as our playground.

We knew nothing of its past but we celebrated birthdays, anniversaries, new births, Eid celebrations, Christmas dinners sprinkled with my mother’s spices. My brother and I only played in the summer, we battled with each other, until someone got hurt and the other one cried. We created paper swords and paper hats and when we got bored, we invited my English friend, Tracy down the road. Her mum was Welsh, she had a different language, like us. Mum would make us our favourite, milky English tea and a few broken biscuits and we would sit on the edge of the brick wall in the entry, hanging our small legs.

I was there, in glass windows and brick walls,

begging on the streets for Penny for a guy, watching the fireworks display light up your new city, eat a halal Christmas dinner, sprinkle grandma’s spices – a taste

we’ve been trying to recreate, even if we tried. Soon my scouse accent lingered on my tongue,

I wanted to feel wanted like that and I made sure

I did. But I slept with my mother’s voice in my ear Never forget where you came from.

In my broken Arabic: This is all the home I need.

A little ginger boy down road, ‘Ey, where do you really come from?’

I, picking at my skin, scarred with mosquito bites

to remind me what is marked, shall never be forgotten.

In my perfect broken scouse, I come from here.

He looks down at his hands, ‘But you look different’.

By sunset, I mapped the world across my body, not finding where to place myself.

We never meant to start a war, so I nodded and smiled and we played piggy in the middle with his friends.

East or West – I had no choice but the piggy was the safest place to be.

Girls like us, settled in a foreign place,

we buried our mother’s tongue in our back gardens, to find the roots outgrown even deeper.

A sacrifice that haunts you every time you sing

your mother’s anthem. But you keep on dancing.

Dad swore he would never marry a village Yemeni girl. He liked Chantelle, they met at the youth club in Lodge Lane, Toxteth. He said, she was the blonde hair and blue eyes to his soul. I cringed, watching at my mum’s reaction over the kitchen table. Mum didn’t say nothing, it was never going to happen in our world. Mum comes from a tribe of businessmen who ruled the town. Dad’s tribe was a refugee, they had escaped persecution and sought asylum in a nearby village. They say they were related into families of royalties, some connection to queen Sheba and her family. I don’t believe him. They are embarrassed to say, they were a farmer’s child.

We danced together with my hair in her hands. I turned my face away.

‘I don’t want to be here mama; your village is my city. My sky is political, its raging and raging’.

My mother chokes up a child-like laughter

and drenches me in olive oil. I hated the smell.

My jet-black hair falling down my back, too thick to carry, too different.

I felt my neck snap. You think you are liberated, but you are only a visitor in an occupier’s land.

She spreads the excess of olive oil across my pigmented neck.

Searching for home, stranded in wars between two houses.

I broke my voice, the crackle over the phone, this home does not exist without you.

I am sick, homesick.