Intellectual meanness procures satisfaction to the minds of those who enjoy inflicting emotional pain with the intention of causing feelings of inadequacy in a victim. Intellectual meanness requires a double talent: that of aiming correctly, and that of fittingly expressing meanness in a visual or verbal medium. The greater the wit with which meanness has been expressed, the greater it grows in acceptance, even in prestige, and thus becomes established as the ritualisation of moral injury – an activity at which the French critical mind excelled. ‘What a man could have been [Honoré de] Balzac if he only knew how to write’, quipped Gustave Flaubert. Speaking of dramatist Victor Hugo the novelist Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly bellowed: ‘You can relinquish the French language, and it will not complain because you have sufficiently tired it out. Write your next book in German’. Referring to the members of the French Academy, writer Georges Bernanos wisecracked: ‘The day when I will have but my buttocks to think, I will sit them down at the Académie’. Such mean jocularity made the fortune of satirists from Apuleius, Horace and Juvenal, to Al-Jahiz and Tha’alibi, to Giovanni Bocaccio and François Rabelais, to Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe, to Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin, to George Orwell, Aldous Huxley and Joseph Heller, and a proliferation of recent television programmes.

Meanness can be developed into an art and can become accepted as an art by artists who gratify their adulating public with their personal opinions. Meanness becomes a form of entertainment that operates on the principle of the emotional elimination of the other. An increase in artistic meanness is also accompanied with an increase in the demand for such meanness. The more humour is allied with insolence, irreverence, irony, cynicism, sarcasm, mockery, sadism, and above all, iconoclasm, the more of it is needed. Intellectual meanness reaches particular effectiveness once the visual and verbal arts combine as they do in paintings and their titles, in caricatures and their captions, and especially in the ever-present empire of television. Mean and cruel thought, ever a companion of criticality, is probably as old as humanity itself. This disquieting phenomenon links the mural painting entitled The Universal Judgment by Giovanni da Modena in Bologna (1412-1415), Andrés Serrano’s cibachrome print known as Piss Christ (1987), and the cartoons collectively published by Charb, Cabu, Tignous, Honoré, and Wolinski, at Charlie Hebdo (in particular since 2006). In the terrible events in Paris on 7 January 2015 the issues of artistic freedom, the freedom to offend, and extremism were confronted in a most agonising way. Understanding these events requires an intense historical knowledge of socio-political ills, but the present essay concerns itself only with the artistic expressions of mean thought.

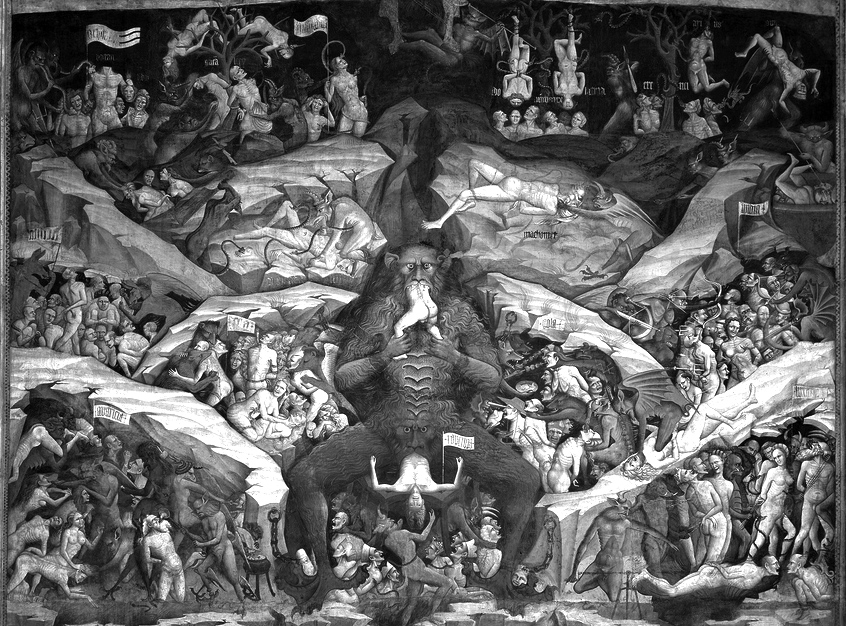

The Universal Judgment by Giovanni da Modena

San Petronio, Bologna’s magnificent and still incomplete cathedral, contains the Cappella dei Re Magi (the chapel of the Three Kings), also known as the Cappella Bolognini. This fourth chapel from the entrance – to the left of the nave – conserves almost intact the original murals of Giovanni da Modena who painted a three-part cycle: The Consecration of San Petronio in the middle wall over the altar; The Universal Judgment on the left wall; and The Story of the Three Kings on the right wall. Giovanni da Modena painted the cycle between 1412 and 1415 at a time when the papacy and Christendom were assembling, in vain, their military forces to launch another crusade with the intention of preventing the Ottoman expansion in the Balkans and in order to save Constantinople. The Universal Judgment, arguably the most renowned and at the same time, infamous of the murals, is composed of three registers, with Paradise on the top and Hell at the bottom. The hellish part of the mural depicts a well-known passage from Canto XXXVIII of the Divine Comedy in which Dante calls the Prophet Muhammad a disseminator of scandals, blames him for the schisms between religions, and relegates him to the bedlam of heretics. Dante condemns Muhammad to an eternally sorrowful path along which his wounds will temporarily heal but only to be reopened with sadistic blows dealt by a sword-wielding devil. Additionally, Muhammad’s head was to be severed from his body, and Giovanni da Modena depicts this lugubrious act being completed by yet another very industrious devil. In 1998 seventy-three homeless immigrants occupied a part of the cathedral of San Petronio for twenty-four hours in protest against the mural during the Muslim Feast of Ramadan until the police disbanded them. Following this event, the president of the Muslim Union of Italy asked for the demeaning and violent depiction of the Prophet Muhammad to be erased from the mural. This demand was rejected by most of the Muslim community in Italy as well as the Italian authorities.

In 1987, New York artist Andrés Serrano won the competition for the Awards in the Visual Arts held by the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art – a competition that was partially sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts. Known as the Piss Christ, the work was a photograph of a plastic crucifix submerged in a glass that contained the artist’s own urine. Many, including myself, found the photograph to be profoundly offensive and vilifying – which was no doubt Serrano’s manifest intention. Many, including myself, decided that the best way to deal with this kind of expression was to ignore it. But ignoring this image poses difficulties in an age where the dissemination, or rather proliferation of images on a vast scale is fervently linked to the belief that artistic freedom has no bounds and should never have any bounds. One’s daily consumption of countless images is only partially conscious, partially voluntary; and much of it requires an unavoidable participation into which one is unwillingly drawn. The images associated with commercial advertising are an example. The daily blitz of images is of such intensity that one rarely has the respite needed to sift through them, and one is forced to make immediate judgments regarding which image to dismiss on account of it being aesthetically or morally displeasing, or to mentally retain it on account of it being aesthetically or morally gratifying. Ignoring artistic expressions that one finds aesthetically or morally condemnable is no easy matter; it requires sustained and disciplined restraint. Much opposition was voiced in the United States to the Piss Christ, and the reader may recall that one US senator vehemently denounced the vulgarity of Serrano’s work before tearing up a photographic reproduction on the Senate floor. In 2007, another photograph of the Piss Christ was vandalised in an art gallery in Sweden by a group that claimed to be on the far right politically; and on 17 April 2011, the same photograph was destroyed using a hammer and pickaxe in the Musée d’art contemporain in Avignon. The exhibition was part of the Collection Lambert entitled Je crois aux miracles: I believe in miracles. More than one thousand opponents demonstrated in Avignon, and thousands more Catholics signed a petition to remove the photograph from the museum. The local bishop, Jean-Pierre Cattenoz, declared: ‘I cannot approve the destruction of this work… but we have demanded that this work be simply withdrawn. If someone spits or ‘pisses’ on me, I would know that I am being disdained. Similarly, to exhibit as a work of art that which for us Christians is a sign of disdain toward the Cross is grievous’.

As a successor of the banned satirical journal Hara-Kiri, Charlie Hebdo took aim at many social and political dimensions of French society with satirical cartoons, irreverent jokes, and jarring news polemics. (Hara-Kiri, also known as L’Hebdo Hara-Kiri, was founded in 1960 by François Cavanna and Georges Bernier and soon employed France’s most vituperative satirists. It was banned twice in 1961 and 1966 for its offensive caricatures and language. President Charles de Gaulle’s death in November 1970 in his native village of Colombey-les-deux-églises occurred a few days after a fire in a discothèque took the lives of nearly one hundred and fifty people. The editors of Hara-Kiri, deciding to satirically comment on the French media’s frenzied coverage of the fire, published a cover headlined ‘Tragic Ball at Colombey, one dead’. The journal was banned again in 1970 and changed its name to Charlie Hebdo in order to circumvent the ban). With relentless obsession, especially since 2006, the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo (the self-described ‘journal irrésponsable’) employed themselves in depicting Islam and the Prophet Muhammad in degrading cartoons. One cover page was headlined ‘The Koran is sh..t’ with a cartoon depicting bullets piercing both the Qur’an and a man holding it with a caption pointing to the Qur’an saying that ‘It does not block bullets’. Another cover page titled ‘The film that enflames the Muslim world’ illustrates the Prophet naked and laying on a bed with a cameraman behind him. With buttocks prominently displayed to the camera behind him, he says to the viewer ‘And my thighs. Do you like my thighs?’. The cartoon suggests that the Prophet is the protagonist in a pornographic film while the cameraman, in apparent disgust, covers one eye. A third cover illustrates pregnant and angry African Muslim women demanding that their welfare rights not be touched. The cartoon occurs under a cover headline that identifies these women as those that had been kidnapped by Boko Haram in order to make them sex slaves, but the title and the cartoon suggest that the women’s anger was not at being enslaved but rather at the reduction in their welfare benefits, in reference to African women living in France.

In 2006, Charlie Hebdo reprinted the infamous twelve cartoons of the Danish journal Jyllands Posten and added several new ones, resulting in a dramatic increase in its copies in circulation. Following many demonstrations against the journal throughout France, President Jacques Chirac and several ministers and public figures condemned Charlie Hebdo’s provocations and called for a wilful avoidance of offending the religious convictions of others. Presidential hopefuls Nicholas Sarkozy, François Bayrou, as well as François Hollande, expressed their support for freedom of expression as one of the foundations of the values of the republic. Three Muslim organisations sued the journal for defamation, and in particular for two of the cartoons that conflated Muslims in general with extremist Muslims, but the journal was acquitted because the court concluded that the journal intended to offend the fundamentalists and not Muslims in general. The leadership of the CFCM (Conseil français de culte musulman) declared that it was hoping for a ‘symbolic condemnation’ in order to discourage those who are engaged in the clash of civilisations from further provocations. ‘Muslim federations are constrained to appeal to the judiciary given the absence of dialogue. Judicial action is our last resort’, said Mohammed Bechari, president of the FNMF (Fédération nationale des musulmans de France).

The murals in Bologna occurred at a time of terrible ethnic and religious antagonisms, and any observer of current affairs cannot but feel the dreadful return of these hostilities which one had hoped had been superseded by an increased tolerance between cultures. But beyond open hostility toward Christianity and Islam, the cibachromes of Serrano and the cartoons of Charlie Hebdo operate on the basis of an artistic phenomenon that has long been accepted as part of modernist art, namely shock value. The main value of shock value is the emotional charge that it delivers both to the artist and the approving observer. This emotional charge is like a bad infinity, being continuously fuelled by the renewed momentum of the emotional charge itself. Consequently, a gradual increase in shock value is needed by a consciousness ever in demand of expanded emotional charges, and ever dissatisfied with the level of shock value itself. Too little of it is disappointing because the anticipated satisfaction was only partially reached. The phenomenon eventually leads to extremes, as both artists and their approving followers grow in their acceptance of artistic expressions that were previously considered extreme. Shock value then becomes an imitative quality as more artists and more viewers wish to express shock value for themselves. In this case, visual perception insistently participates in the formation and development of a desire for more shocking images and words. Shock value succeeds because it is a form of desire, an addictive desire to pass beyond irritation, to provocation, to incitement, to enflaming, to insulting, to humiliating another – all in the name of freedom of artistic expression. Artistic freedom, here, has come to be equated with a freedom to offend. Swiss intellectual Tariq Ramadan qualified the work of Charlie Hebdo and Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier, the chief editor of the journal) as un humour lâche, a cowardly humour, because these artists hide behind the law while hurling insults against others who are then condemned for being insulted by the offense. Naturally, none of this justifies the arson at the offices of Charlie Hebdo in 2011, or the murder of their cartoonists by the extremist Kouachi brothers in 2015.

When no extreme positions are disturbing the world of art many intellectuals make no trenchant opinions about limitations to artistic content or the limitations to socio-political expression in the arts. In fact these same intellectuals wish to maintain an ever-expanding range for artistic freedom, particularly in a society that claims democratic pluralism as one of its most valued virtues. They associate democratic pluralism with political freedom and with artistic freedom. Although both freedoms are not the same, it is usually held that political freedom encompasses artistic freedom, in the sense that political freedom is a necessary condition for artistic freedom to flourish. Even when artists abandon propriety and temperance and begin to pursue rupture and transgression, intellectuals still affirm political and artistic freedom because it is better to have artistic transgressions than to imply that artists should self-censor, or worse still, to imply that institutions should impose a form of artistic censorship. Citizens should not find themselves fearing censorship. And yet…and yet, that very same French society that prides itself on its tolerance of conflicting opinions proffers severe punishments on those who insult the nation, the head of state, national symbols like the flag, or whistling during the recitation of the Marseillaise.

But when some artists adopt the position that rupture and transgression should constitute the very theory that guides their daily practice, it is quite possible that the artistic and political content that qualifies this work becomes extreme. Here, intellectuals are faced with a difficulty and their judgments begin to divide. Some, faithful to the old call for shock value, actually welcome extreme expressions. Others, will remind the public that art has had a decidedly confrontational role since the French Revolution’s call aux armes, aux arts was used to justify politico-artistic belligerency, leading to the storming of the Bastille, followed by the storming of the academic Bastille. Some will decide to tolerate some transgressions while turning a blind eye to others. Others still, might be intimidated by artistic extremism and prefer to look the other way.

Fewer intellectuals will judge the transgressive quality of the art itself in relation to its mean effects on society and on the artistic image itself.

But even if intellectuals may not take trenchant positions, extremist artistic productions compel artists themselves to take a position on the limits of expression in the arts. Ordinarily most artistic productions are considerably more temperate in their socio-political content than the work of the satirists at Charlie Hebdo. So we are not comparing amusing satirical work versus non-amused observers, although most readers who disliked the work, including French Muslim readers, simply decided to ignore it. We are instead comparing extreme provocations that are artistically expressed (Charlie Hebdo) and extremely violent reactions to them (the murderous Kouachi brothers). This is not the old struggle between iconoclasts and iconophiles. Nor is it a conflict about the artistic freedom of expression versus those so intolerant of artistic expression that they are prepared to murder the artists themselves. Rather, it is on the more basic level, or rather base level, of emotional rawness where artistic extremism collided precisely with the violent extremism it has been actively taunting for years. The streets of Paris became the tragic theatre for this fatal embrace of extremisms. The caricaturists were extreme in their relentless affront and humiliation of certain religious beliefs by knowingly provoking those who adhered to the most extreme interpretations of their faith. The Kouachi brothers were extreme in their intention to vindicate the affront by committing the crime of killing the artists, as if murder somehow re-establishes the balance with respect to demeaning images and words. Although intellectuals in democratic societies will rarely admit it, the image and the word can still provoke violence; and let us not forget the verbal violence uttered by art critics.

Artistic freedom can also be turned into an abuse of the artistic image, and although the work of the caricaturists of Charlie Hebdo shares a tenuous relationship with the rich tradition of the bandes dessinées in Belgium and France, they are very far from the refined artistry of an Hergé (Tintin), a Jacques Martin (Alix), an Edgar-Pierre Jacobs (Blake et Mortimer), and even Goscinny et Uderzo (Astérix). In their stimulating stories these artists suggested social reforms and sometimes engaged in irony and satire with sharp humour. But with few exceptions, they rarely descended into bad taste or insulted the other, where otherness is understood as being inferior. Their work still upheld propriety (the Latin decor, the French convenance) in the sense that they voluntarily practiced temperance using their art as a departure point with which to look at society, and then looking at their own art taking society as a beginning point. In so doing, they used their art in order to build a common culture. Art can be used to build the City, the moral edifice in which we share our political life with the aim of living together justly. The fact that many artists have abandoned this aim is all the more reason to reaffirm it. The artistic practice of mean thought will certainly continue to give satisfaction to its authors and their public who can suspend propriety for the purposes of bathing in the relativist flux of entertainment empires. But if art is to express another of its roles, in particular its welcome reformatory and educational tasks, then it is more likely to achieve these tasks by appealing to the intellects and moral judgments of the citizenry, and their tolerance of the other.

— Reprinted, with permission, from America Arts Quarterly Summer, Vol. 34, Nº3, 2015.