Norhayati Kaprawi, or Yati, as she is affectionately known, is a Muslim woman artist-activist from Malaysia. Trained as a civil engineer in Wales in the 1980s, she transitioned into full-time activism in the early 2000s. Her work involves engaging with grassroots women’s communities so that they are aware of the full range of their rights within Islam, many of which have been systematically withheld by Malaysia’s Islamic bureaucracy because of its patriarchal, restrictive interpretation of the religion. But her activism is far from dreary – her sense of humour and lightness of touch always bubble up. In order to gain the trust of one village community, for example, she spent hours with the menfolk, stirring communal dodol, a traditional toffee made from the aromatic durian fruit, until everyone was charmed by her wit and passion.

Through her activism, she caught the filmmaking bug, and has now made numerous documentaries on topics such as the tudung (headscarf), Muslim women ulama (scholars), and religious conversion and child custody, all fraught issues under Malaysia’s Syariah legal system. She takes it upon herself to screen her films at university campuses and independent festivals around Malaysia – often to packed halls.

Her first love, however, is painting, as she explains to Critical Muslim Deputy Editor, Shanon Shah. They have been friends since the early 2000s, when both were actively involved Sisters in Islam, the Muslim feminist non-governmental organisation. In Yati’s words:

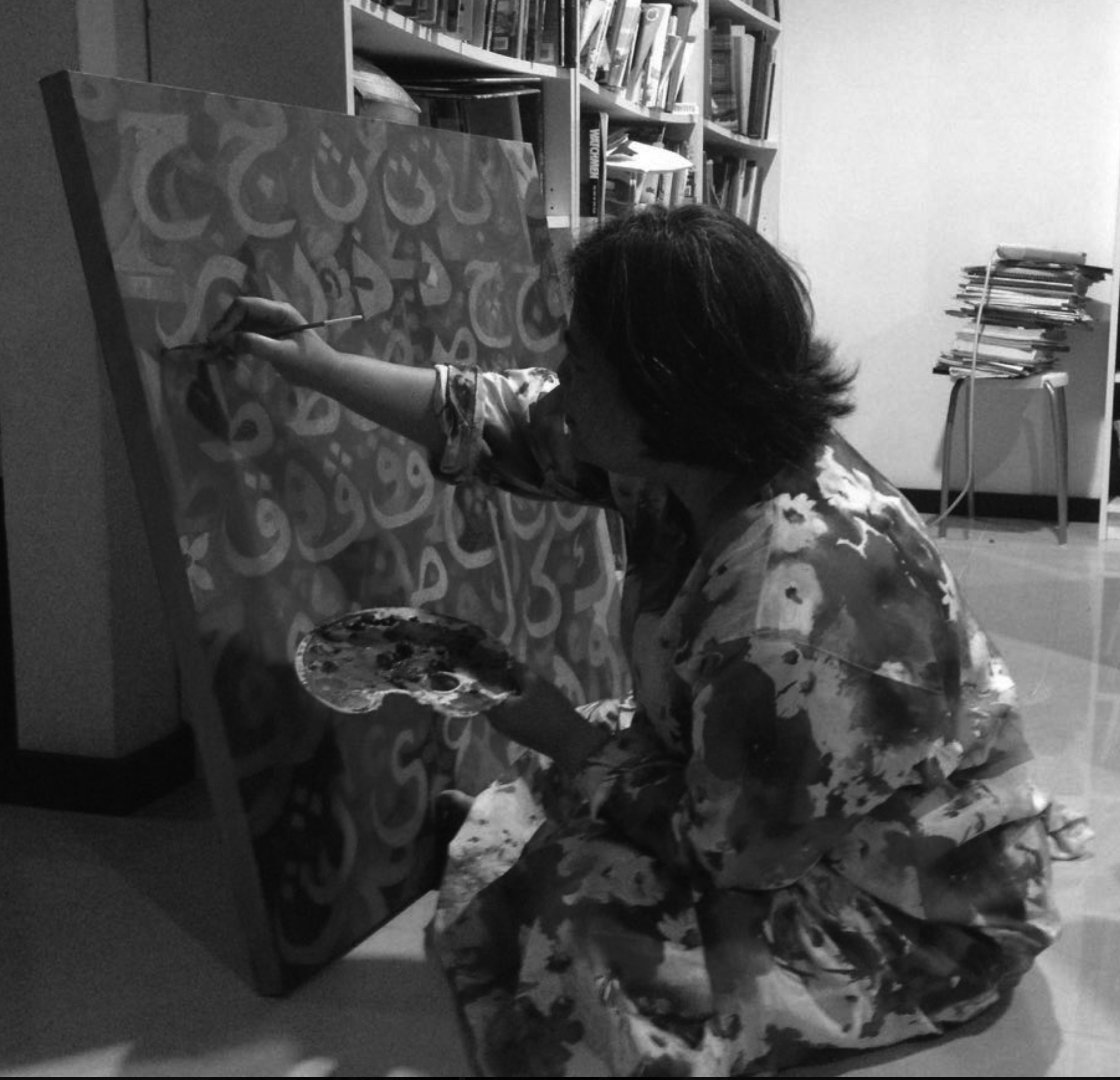

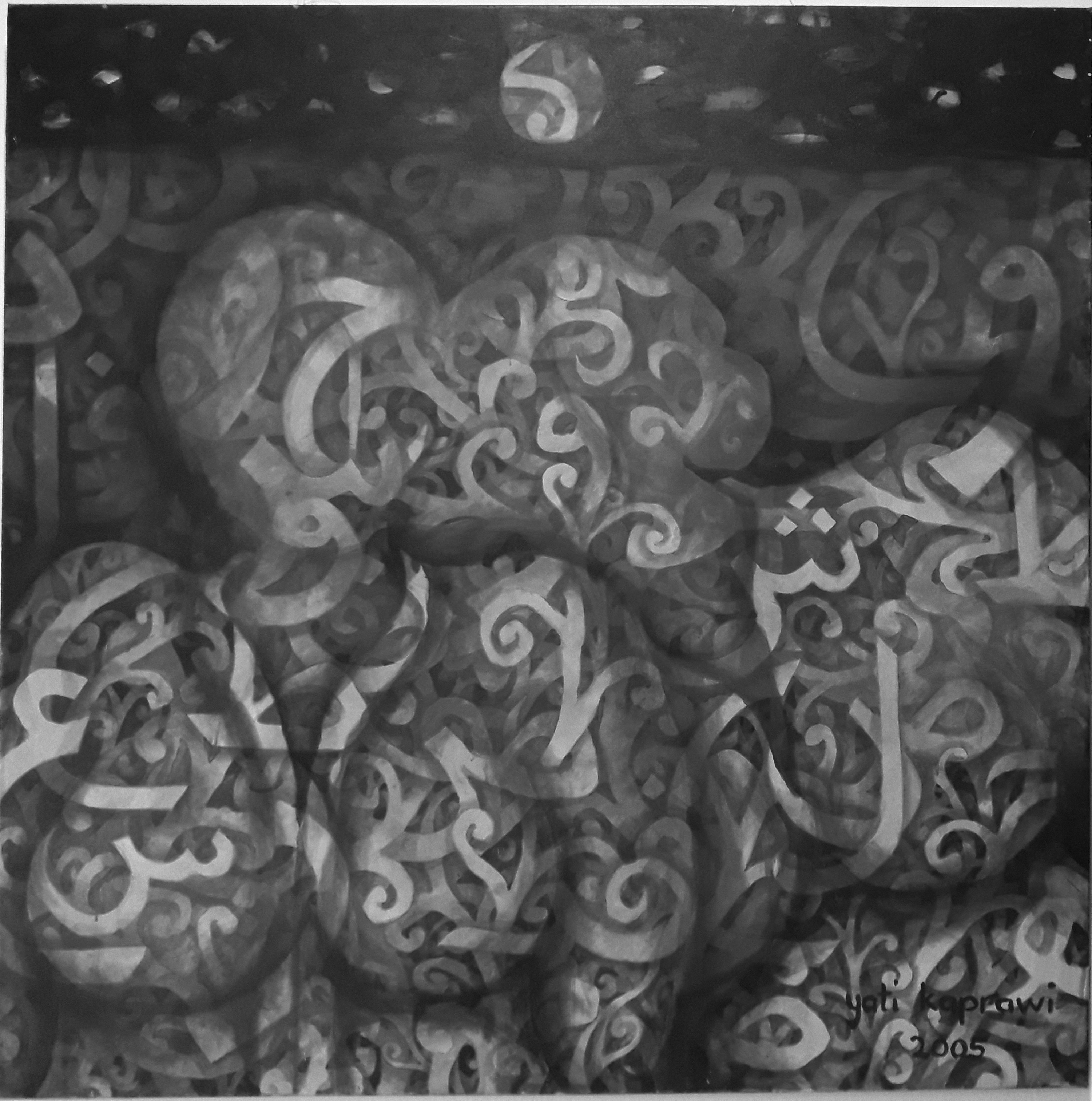

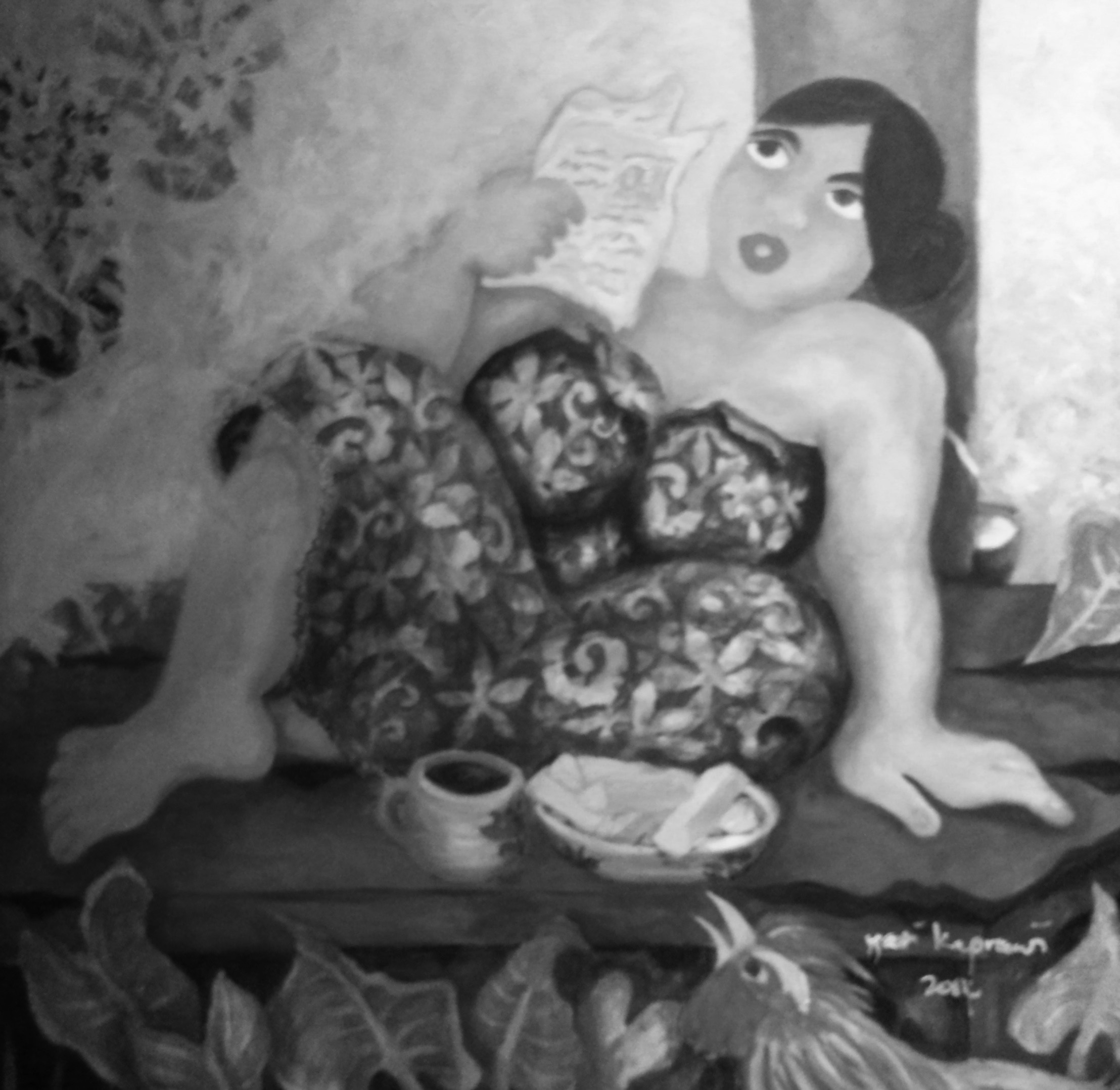

My paintings have primarily explored two themes – batik jawi (or the Arabic-influenced batik of the Malay Archipelago) and kemban (the traditional Malay women’s torso wrap). But I don’t feel that I have to be bound by any particular style of genre. I love Jawi (the Arabic alphabet for writing the Malay language) because I am from Johor, the southernmost state in Peninsula Malaysia, and we were all taught to write in Jawi from young. I went on to take a short course on khat (Islamic calligraphy) at the Islamic Arts Museum in Kuala Lumpur. But I don’t produce ‘proper’ khat – I use it as a concept to create more abstract works. And I absolutely love batik because my first venture into visual arts was making batik prints on silk. When I got busier, I started painting on canvas, but using the batik-making style and approach, without the use of wax. I integrate Jawi and batik because I want to convey that religion and culture are often intertwined and inseparable. Sometimes I add the element of human relationships, in whatever form, because they are part of the signs of nature that the Qur’an encourages us to appreciate and reflect upon.

Motivasi (Motivation) This is for lazybones like me. It’s inspired by a friend of mine whose mother saw her sprawling on the sofa while watching a Jane Fonda exercise video. The mother said, deadpan, ‘Right, at this rate, you’ll be losing weight in no time.’

Picnic This is how my family used to do picnics – go to the park, eat, and lay down the rest of the afternoon. We wouldn’t take walks – we’d watch other people take walks.

Oops When I was a child, my siblings and I used to bathe in the pond near my uncle’s house in our village. My sister’s sarong would balloon upwards every time she jumped in.

Love I don’t feel like I have to be bound by any particular style or genre.

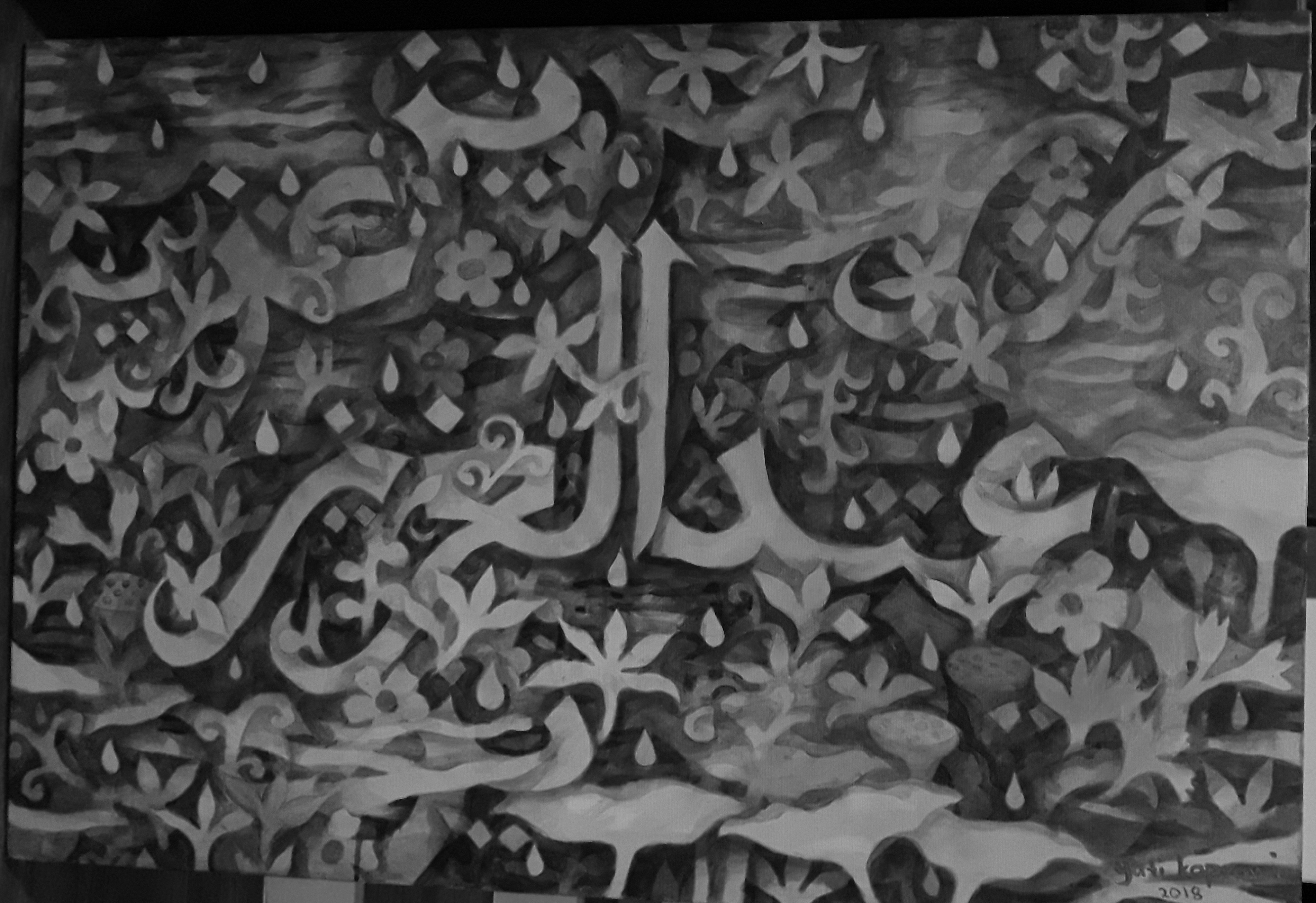

Abdul Aziz This is a painting requested by my sister in memory of her late husband, my brother-in-law.

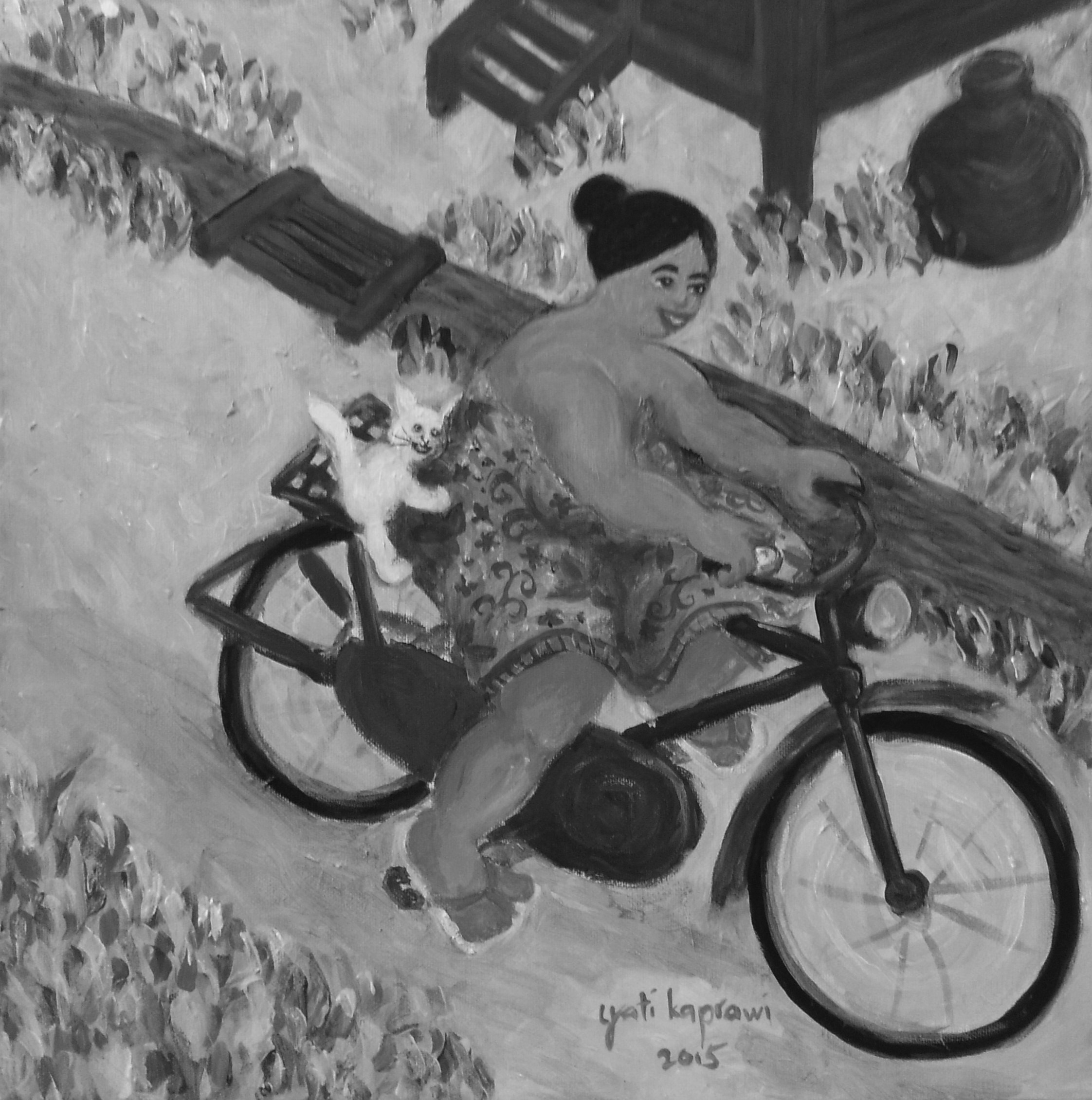

Bersiar dengan Miaw (Gallivanting with the cat) I sold this at a charity event organised by a trans woman activist, Nisha Ayub.

Panas sungguh (It’s too hot) This was sold at another charity event, organised by the Women’s Aid Organisation.