1st Postcard from Murad

Before breakfast, I walked back to last night’s perfumed bush. It wasn’t fragrant now: I must have smelt a night flower. We breakfasted beneath an orange tree. By the Alcazar gate, a chamber orchestra played the Habanera from Carmen. Only oranges and songs to take away.

We are leaving Sevilla. The bus station is crowded, proletarian. My companion wants water, a ham roll, the Ladies’ loo. I fear we won’t board on time.

A skirmish for seats, but they’re numbered. We leave on schedule: midday on an August Tuesday.

1st extract from Refika’s notebook

All those rainy London nights in Noura, Ozer, Melati and Taro when we’d plan our visit to Granada over leisurely dinners, how we might find the heart of who we were, this long-lost European Muslim civilisation, a place fragranced with orange blossom, whose existence challenged the clichés about two unbridgeable civilisations. Should we see the palace in the early morning or should we see it in moonlight, when there was less of a crowd? We already hated the other people we’d have to share the Alhambra with. It was our imaginary palace, far from our complicated lives with the clutter of difficult divorces, custody battles, demanding jobs, family feuds and disputes about inheritances.

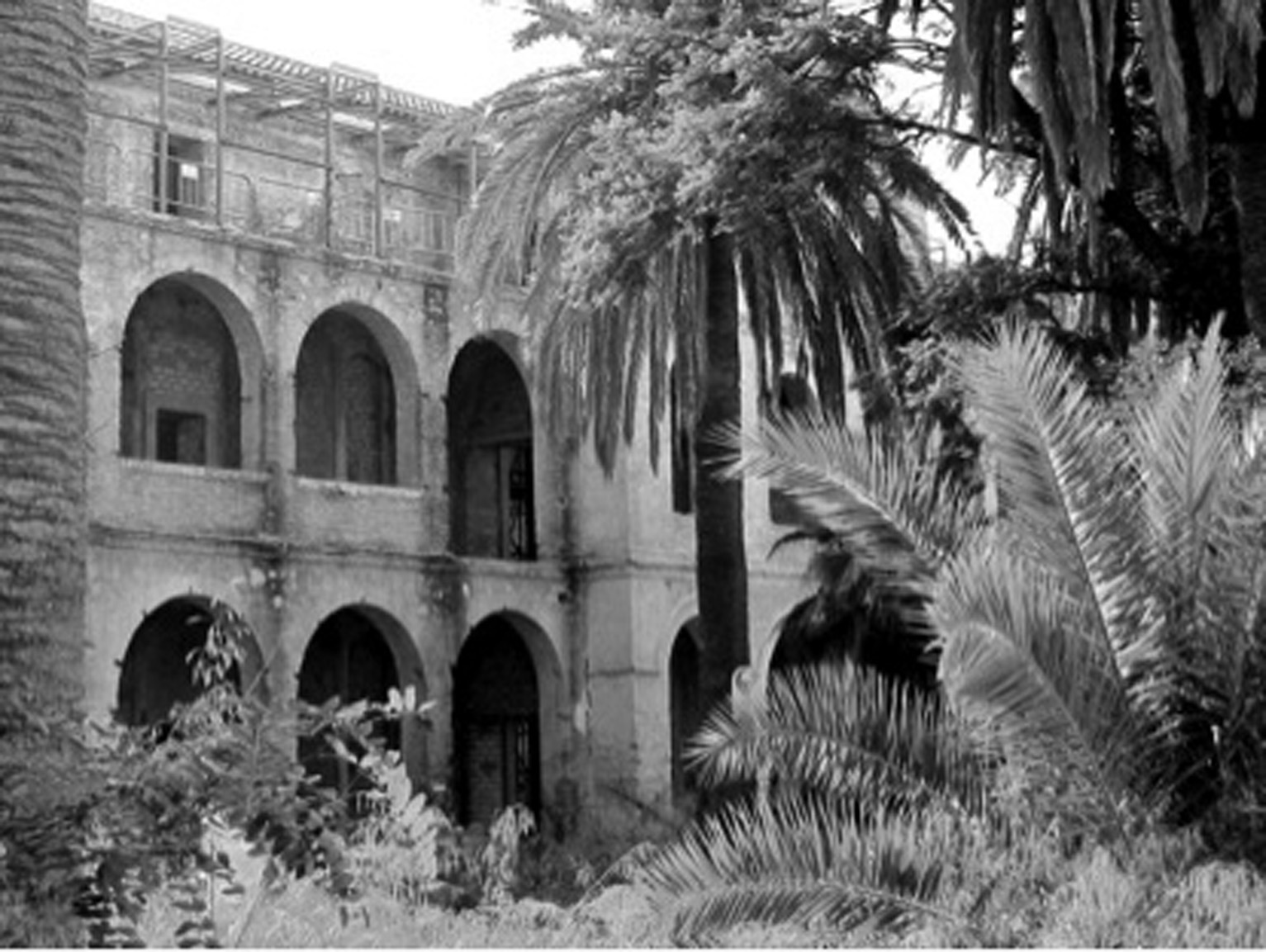

All that talk came to nothing. The website that sold the tickets crashed. The hotel directed us to a travel agent down a long hot thoroughfare that stretched listlessly in the dusty heat, revealing the city’s plain everyday face, a motorway, a dusty curb, rubbish. The travel agent was not only shut it had closed down, deserted like all the other shrouded shops.

We had Seville and the Alcazar instead. I was confused, which parts of the palace were Islamic, which Catholic aftermath? It didn’t seem to matter. I couldn’t imagine anyone actually living there. The gardens were loveliest. Reversed perspectives and geometries.

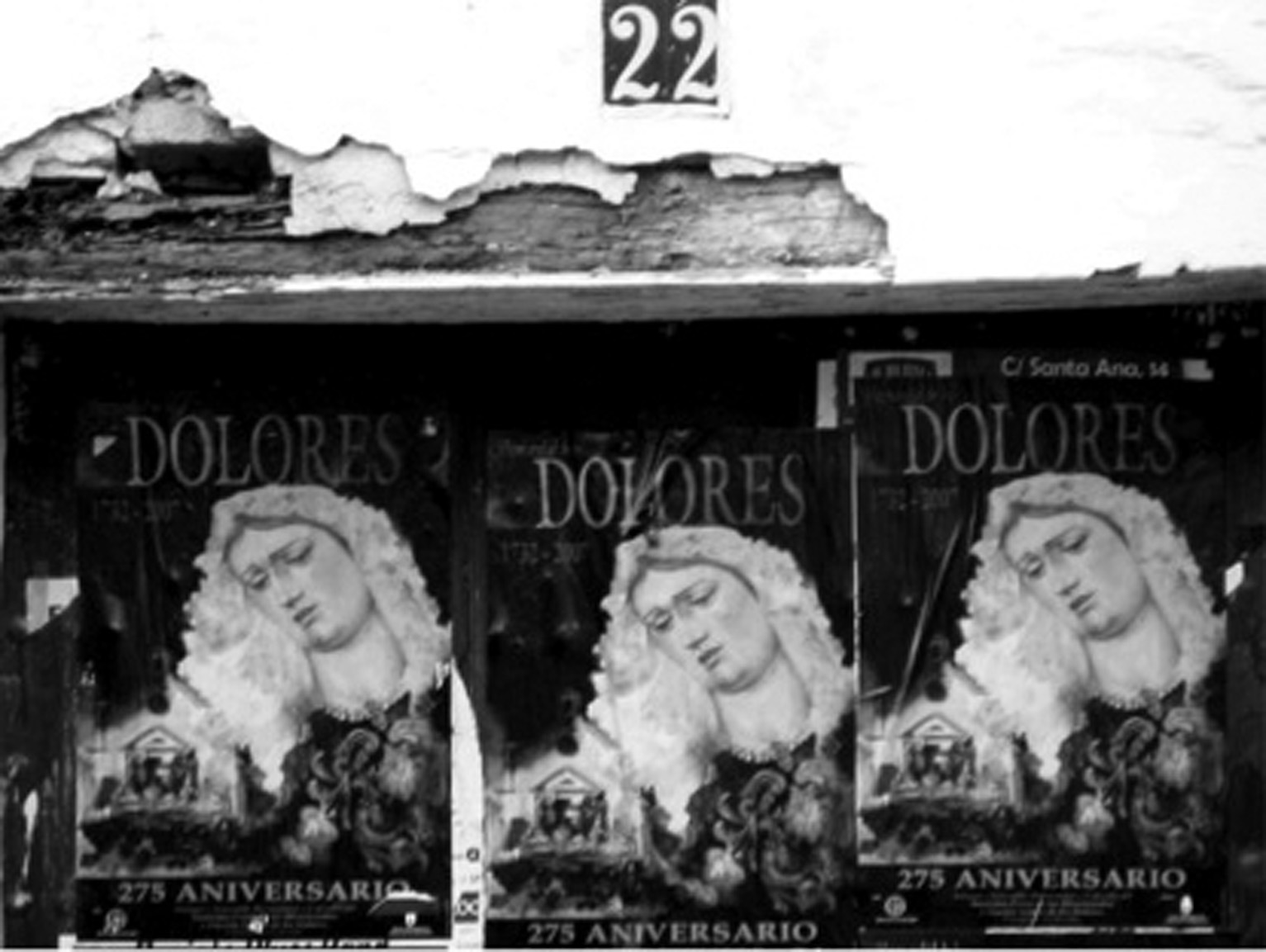

A weeping Madonna on the street. Inez Rosales tortas de aceite wrapped in greaseproof paper decorated with florid navy ink, flaking crumbs of anise and orange, tastes of North Africa on my lips. At breakfast I read Tales of the Dervishes by Idries Shah, its thirty-year-old cover once vibrant orange now a faded yellow. Murad writes a postcard.

‘Whom are you writing to?’ I ask him

‘That’s difficult to say,’ he tells me.

2nd Postcard from Murad

On board, a confusing text on my companion’s mobile. We try to calm each other: aren’t we expected in Sanlucar? Is there some misunderstanding? Dun landscapes from the window.

The journey’s shorter than expected. God, the vagaries of making electronic contact. My irritation makes my travelling companion laugh out loud.

I stole the term ‘companion’ from Pavese. In real life friends are all that matter, but ‘friend’ in a narration sounds coy.

Perhaps we laugh together.

2nd extract from Refika’s notebook

I have passed through beautiful train stations like palaces, eaten oysters in Grand Central, seen the faded Ottoman majesty and stained glass windows of Sirkeci in Istanbul and watched gulls reeling outside the tiled splendour of Porto station, but bus stations have been tired ugly places in my experience. I’ve never encountered a charming one. Seville’s is typical in its random concrete squalour and the pervasive smell of drains.

I spend a lot of time in bus stations in my nightmares. Bucharest, Ankara, Istanbul, Vienna, too often in the rain. Also at intersections on motorways, walking where there are no pedestrians, knowing I am once again in looks-like-Birmingham-but-is-really-Belgrade. I have never been to either city in my waking hours. My dreaming self is thirteen years old, if we suppose I sleep a third of my life. Her restless teenage soul prowls ugly peripheries and arteries, motorways and underpasses, refusing to return me to the real palace gardens I have seen.

3rd Postcard from Murad

My Spanish sister – I call her that, she calls me hermanito – is waiting at the little station. We have come to her for her birthday. She drives us to her new house: full of light as homes should be, with airy windows.

A year ago, she painted me, in oils. I’m dressed in blue and larger than life, sitting by a window of her London flat. Behind me there’s a red brick wall. She complained of London’s changing autumn light. Here she paints in her eyrie, in a tower. Her studio overlooks tall palms, jasmine bushes, bright flowers.

Later, with green figs, white peaches, local cheese, we drink summer wine. My sister calls it poor man’s sangria.

3rd extract from Refika’s notebook

We drove down the long avenue of cypresses hidden behind the tall dark green gates. For three consecutive Augusts we went to San Lucar to celebrate the Princess’ birthday. Murad was her guest of honour, she called him her little brother. We drove down the long avenue to the new house in the old botanical gardens.

The first year we ate in the gardens at white damask-covered tables that shone silver under the full moon. The trees were ripe with butterfly lanterns.

The second year the women danced the Sevillana, their hands a forest of swooping circular gestures, a language I almost spoke, but not at all fluently, as I discovered when they insisted on drawing me into the dance.

The third year it rained incessantly and the party was held in the old eighteenth-century tower. Black umbrellas hung from the porch like malevolent bats. That was the year Death came with me, thought I could use the company.

4th Postcard from Murad

Satiated, seated by the blue pool now, hot as heaven. Anxieties disperse, join red petals scattered round on stone and grass. Birds dip their beaks in the pool’s water. In the sun’s blaze the leaves on their branches shine white. Now I think of the garden I once called home.

Shirtless, I lie on short grass. Its texture tickles my back. My companion, swimming, leaves me to my lonely thinking. (Once we shared summer ruminations. At times our silences run parallel. At others we’re like strangers who don’t meet.)

The cuckoo calls three times, as brazen as a rooster. Perhaps the sun estranges thoughts, reminds me of advancing age, grey hair, dull flesh. Still, in dreams, I fly before I fall.

4th extract from Refika’s notebook

Murad is reading Pavese. The row of palms behind the tennis court is almost still. There is no breeze yet the pool wriggles with light. I dive into the blue and try to remember something about Pavese. Razed fields, miles and miles of burnt landscape, but I can’t tell if these are related to something Pavese wrote, a memory of something else altogether or my nightmares.

‘He came to me young, of his own accord’, Death tells me.

I pull myself out of the water quickly as though I could escape my new companion easily, shaking him off with the tiny droplets of water as I walk across the lawn. Soon it will be lunch. There will be gazpacho. The gazpacho is delicious. The cook is famous for it.

5th Postcard from Murad

My sister, dressed in green, is dancing the Sevillana as we enter. Two friends are with her; one dances too, the other sounds the beat with flattened palms. They are sisters.

Sunlight dapples my sister’s cheekbones, flickers on her fine drawn features. She dances with her face.

I’d love to paint her like this, in her green flamenco dress, dancing. If I could paint. But she could paint herself. Tres morenas de Jaen, Axa, Fatma, y Maryen … I.

‘What does duende really mean?’ Someone asked my sister, at a London supper. ‘Duende means talent,’ she responded. ‘It’s not a word we do not use much anymore.’

Tomorrow is her birthday. Her grandchildren are on holiday on another continent.

My sister, my companion remarks, looks twenty when she dances.

5th extract from Refika’s notebook

Death is not good with dates. Time is a problem for him. All of it is happening at once. He tries not to remember everything, but it is impossible for him to forget. So busy all the time, for all of time. His to-do list gets longer and longer. There are seven billion of us now.

‘I meet so few old souls these days,’ he muses. ‘And most of the tigers are mine already.’ The wildness of beauty is on the other side now.

6th Postcard from Murad

Later, on the beach. Pavese called the sea a field. Tonight it is, a silver field. The sky reddens, darkens, scatters stars.

‘We’re at the mouth of the Guadalquivir,’ my neighbour says. ‘The Arabs called it something like wad-el-kabir.’

‘Andalusian hospitality, too, is Arab,’ someone says.

But this is not the sea. The yellow strand is not a beach. I’ll stick to my terms. Sea or river, the line of water remains a silver field.

6th extract from Refika’s notebook

The night air is warm as blood. Dark can be both wave and particle, gentle negation. Death lights my cigarette for me, whispers in my ear. He is in his element. I am barely aware of the dinner table conversation, hypnotised by the dance of reflections on the wine glasses, huge delicate balloons teetering on delicate stalks. Another covert Sevillana, the hands gesturing, lighting cigarettes, the raising and lowering of the glasses. I hear myself telling the table about the barrel signed by Faiz I had seen in the winery today. My voice sounds very far away to me. The Princess tells the story of Faiz’s visit to San Lucar.

7th Postcard from Murad

We eat water-creatures: anchovies and anemones, cockles, langoustines and bream. My neighbour speaks to me of ragged love and separation. My mind and tongue unlock their Spanish. We are, at fifty, childless. My companion, eleven years younger, has a son.

‘You should have a child, the two of you,’ my neighbour says.

‘Ah, I tell her, but we’re not lovers.’

‘We’re best friends,’ my companion adds.

‘Do you still feel Pakistani?’ The Venezuelan to my left asks me.

‘I do, when I feel anything at all.’

The Venezuelan drones on.

‘Muslims in Europe are a demographic problem. In Andalusia, I hear, they want to reclaim ancient sacred places. They should be loyal to their country of adoption. Wouldn’t you say?’

‘I guess I’m a Muslim in Europe too,’ I say. ‘And foreign everywhere I go.’

With one desultory gesture I dismiss an uncongenial conversation.

‘I’m tired of romance,’ I overhear my companion saying.

‘But without love life’s an uphill climb,’ my sister muses.

Now, as I drink manzanilla, I see you in my glass. Perhaps I haven’t thought of you as yet, left you behind with other things in London. Finger dipped in ink of manzanilla, I bring you into being from your place of absence, think of writing you into this narrative. (Like me, I remember, you can’t swim.) Why do we see yesterday as shadow, tell me, call memory a haunting? Echoed crooked smiles, linked fingers, can thrill, become a sudden presence. Should I write: sometimes I think of you and wonder if you really happened, on occasion wish you were here to taste the green figs and the summer wine – B or remind you of an evening’s words that spiralled from life’s work into euphoria, an empty bottle’s cork I kept at dawn, some other things you left behind?

7th extract from Refika’s notebook

‘You could just come with me and forget all this.’ Death says. He would write my name in pomegranate seeds, ‘I love you’ in cocaine. Roses and razor blades are his idea of romance. Death knows how to seduce. They are talking about love now. I turn away from him, to the living.

‘I am tired of romance.’ I say.

8th Postcard from Murad

At midnight we sit on the patio. My sister smokes a cigarillo, I sip brandy poured on ice. A little lizard, startled, runs up the wall. The smell I remember from Sevilla fills the air, from a bush behind my left elbow.

‘Jasmine,’ my sister says.

(I must remember this, to tell you: there’s no frangipani here, that makes it less like Karachi.)

Now it’s nearly 2. My companion has retired to her room, her separate thoughts. (She wanted to visit the Alhambra. Short of time, we couldn’t make it.)

Too often I treat friends like lovers, lovers as friends, give children the attention owed to adults. But friendship’s all that matters. I have no time left for love. (One night B – November, and the moon was full – B you told me we had nowhere left to go. For a while I’d dreamed that we might travel on. It doesn’t matter any more.)

My sister knows all this. I need to tell her nothing. We sit alone together. The sky hangs dark and low. We continue to talk, of small, of necessary things.

‘The frangipani tree I planted will be in full flower the next time you’re here …’ my sister breaks her sentence. Her eyes are very blue.

8th extract from Refika’s notebook

The moon is full tonight. I watch her fanning herself with the palms from my bed. I lull myself to sleep by imagining I am walking barefoot through the red palace that is a pearl set in emeralds, the walls are made of a calligraphy of smoke, decorated with arabesques of remembered gestures, the fountains recite poems, the pools reflect the inky sky. But I know I’ll dream again of motorways.

9th Postcard from Murad

Eyes shut, I breathe in, lost colours found again: jasmine white, fig green, hibiscus red and something new, unnamed: purple, perhaps.

The fan hums overhead. I recall one mad night’s crossing, and a morning salutation: parted lips brush mine four times, and then – B an afterthought? – B a fifth. How should I name so accidental an exchange: inconsequence, or parting gift? What would you say?

Next door, my companion turns the tap on. What, I wonder, woke her? By my pillow, in a vase beside a jug of sparkling spring water, a twig of orange bougainvillea leans on jasmine. Like yesterday, it has no shadow and no smell.

9th extract from Refika’s notebook

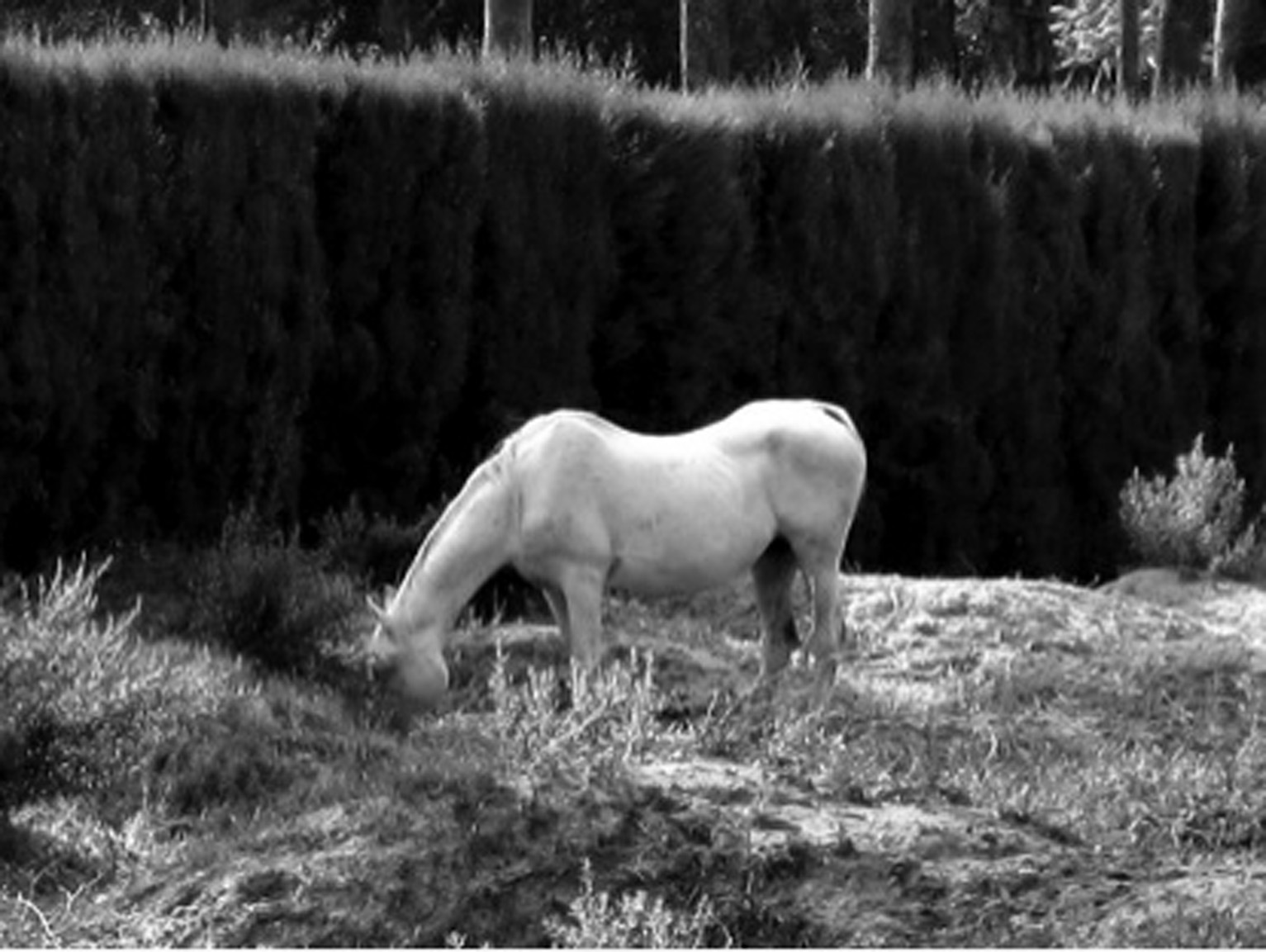

He takes me by the hand. We walk past the barking dogs, the white mare in the tall grass, down the avenue of cypresses, out of the gates, down the winding backstreets of the old town, to the edge of the land where the sea begins. And I take off my clothes and I take off my name and I swim off the page.

Death will come and will wear your eyes

– the death that is with us

from morning to evening, sleepless,

deaf, like an old regret

or an absurd vice. Your eyes

will be a futile word,

a cry kept silent, a silence.

Thus you see them every morning

when alone you stoop over yourself

in the mirror. O dear hope,

that day we too will know

that you are life and nothingness.