Khidr Collective launched its first zine in Summer 2017. The concept began life as an intuitive response to a tangible sense of powerlessness among Muslims. This was coupled with a feeling that a number of organisations were setting themselves up as spokespeople for Muslim communities claiming authenticity to monopolise the narrative. A member of the founding team, Mohamed-Zain Dada, explains the way he and groups within his community recognised the pedagogies that supported this abuse of power and decided they needed to act to redress the imbalance, an intention which manifested in producing the magazine. ‘We are facilitators, writers and artists who want to speak truth to power and cultivate agency, bringing in new voices and harnessing the creativity and potential of the next generation. We decided it was up to us to disturb the echo chamber.’ The end product was a zine that provides a space for reflective stories of joy and resistance from young Muslims across the UK. Named after a character that has captivated Islamic and non-Islamic thought, al-Khadir, or The Green One, the eternal wanderer and seeker of wisdom and knowledge transcends definitions. The group’s emphasis on unexamined aspects of Islamic history is exemplified in their profiling of Khidr. A mysterious, powerful figure, it is fitting that he lends his name to this non-conforming space.

The Collective is fuelled by the enthusiasm of a range of mentors and benefactors who have guided and nurtured the young talent they see around them. Determined to decolonise the language they use and ensure that their content is accessible to everyone regardless of academic credentials, Dada explains that they had to reject some contributions written in academic prose, seeking instead to capture a medium that spoke to everyone. Members of the Collective took to the streets of East London to speak directly to young Muslims in an effort to understand what they felt was lacking from their experience of arts, culture, the media and education. Overwhelmingly they were told that what they desired was representation. This confirmed the intuitive need to counter the dominant Islamophobic narrative and address its impact on young Muslims who feel demonised in such a relentlessly regulatory and normalised way. Young people are negotiating the effects of violence from the state, while attempting to resist the internalised violence of neoliberalism and identity, in a way that their elders and others experienced differently, and responded to differently. Now, this generation wishes to speak truth to power. As stated in its introduction: ‘This zine is an intervention and an opening.’

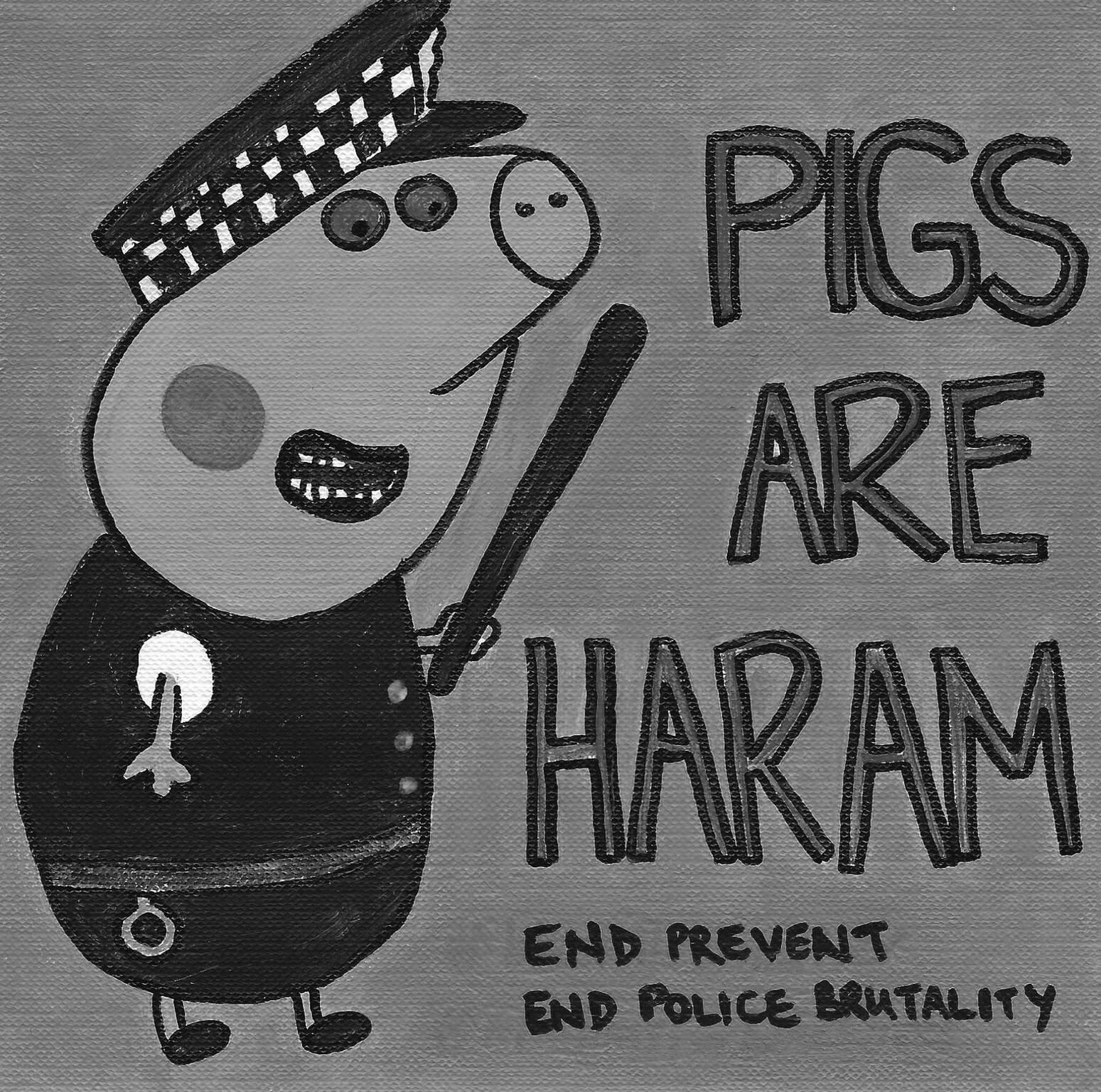

Humour is associated with Islam for all the wrong reasons, even though a rich tradition of satire thrives in the Muslim world. There is such an abundance of injustice encountered by oppressed peoples that sometimes the only way to cope is to be amused. The zine subverts the ridiculous notion that the Muslim world doesn’t do satire because it has no place for freedom of speech. Memes, images and various visual forms articulate the vibrancy of creative thought among young Muslims in today’s challenging geopolitical times.

The founding members of Khidr Collective see themselves as an evolving group consistently interrogating and challenging their own structures so they do not become psychologically or materially dismembered from the body politic and remain inclusive. They are also keen to assert that their team consists of non-Muslims as well as Muslims from a diverse range of backgrounds. The Fillet O Fish illustration was created by Rui Da Silva, who is not Muslim but is an example of someone who, having grown up in a certain marginalised community, has full access to the philosophical underpinning of what it means to be part of that community.

The future for the Collective, according to Dada, is to cultivate voices that would otherwise be silenced. In an insurgent way, they wish to remain outside the echo chamber and access those who don’t have a way ‘in’ whether it is because they don’t share Facebook friends or Twitter followers or know the ‘gatekeepers’. Social media has vast potential for democratisation but can similarly reinforce barriers if access is inflexible. Still in its infancy, Khidr Collective sees itself as a bridge, continuously reflecting, evaluating, facilitating, decolonising and cultivating voices. The second edition of the Khidr Collective magazine launches in January 2018, on the theme of shifaa.

Fillet O Fish: Rui Da Silva

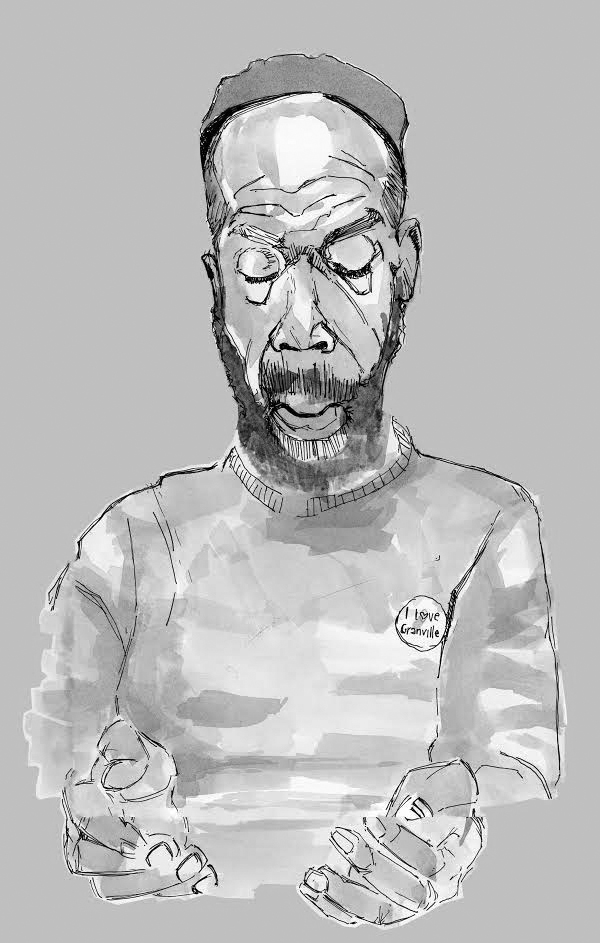

Lone fisherman: Moustafa Hasan

Pigs Are Haram: Lena Mohamed

Shaykh Omar: Nur Hannah Wan