O, the ever-flowing waters of Guadalquivir,

Someone on your banks

Is seeing a vision of some other period of

time.

Standing in front of the Cordoba Mosque, Muhammad Iqbal, the celebrated twentieth-century poet and philosopher of the Indian Subcontinent, had a transcendental experience. It was January 1933; Muslims and Jews were still forbidden from visiting Spain, and Iqbal had to get special permission from the British government. He was transfixed by the ‘aura’ of the mosque , which sits near Guadalquivir, the river that runs through Cordoba. As he gazed at the mosque, his soul was ‘kindled’ and his heart ‘illuminated’. He was moved to write. The ‘Mosque of Cordoba’, a poem of sixty-four couplets, is seen as one of his best poems. Indeed, it has been suggested that it summarises his philosophy. The poem talks about our unending quest for Divine love, our constant search for knowledge, our perpetual desire to be creative. It dwells on the endless chain of life and death, where everything – man, nature, buildings, cultures, art and stories – dies only to re-emerge in different shapes and forms, just as day inevitably follows night. Total immersive dedication and individual attachment to a higher purpose is what Iqbal saw in the mosque. As always, he mines the past to create hope for the future.

He was one of the first Muslims to be allowed to pray in the mosque, which he considered not just as a place of worship but as a work of art that reflected God’s own beauty:

Your beauty, your majesty,

Personify the graces of the man of faith.

You are beautiful and majestic.

He too is beautiful and majestic.

Your grandeur calls to mind

The loftiness of His station,

The sweep of His vision,

His rapture, His ardour, His pride, His humility.

For Iqbal, the mosque seemed to define time itself. It is a place and space of and for stories; the stories of Abraham and Moses, Jesus and Muhammad, a building that witnessed the rise and fall of cultures and civilisations. The mosque radiated with ‘Godly love’, ‘the essence of life’, ‘which death is forbidden to touch’. In the final analysis, ‘Mosque of Cordoba’, like all mystical poems, is a poem of love:

To Love, you owe your being,

O, Harem of Cordoba,

To Love, that is eternal;

Never waning, never fading.

After praising the foundations, columns, arches and terraces of the Cordoba Mosque, Iqbal ends up describing it as ‘Mecca of art lovers’ that elevates a parochial place called Andalusia ‘to the eminence of the Holy Harem’.

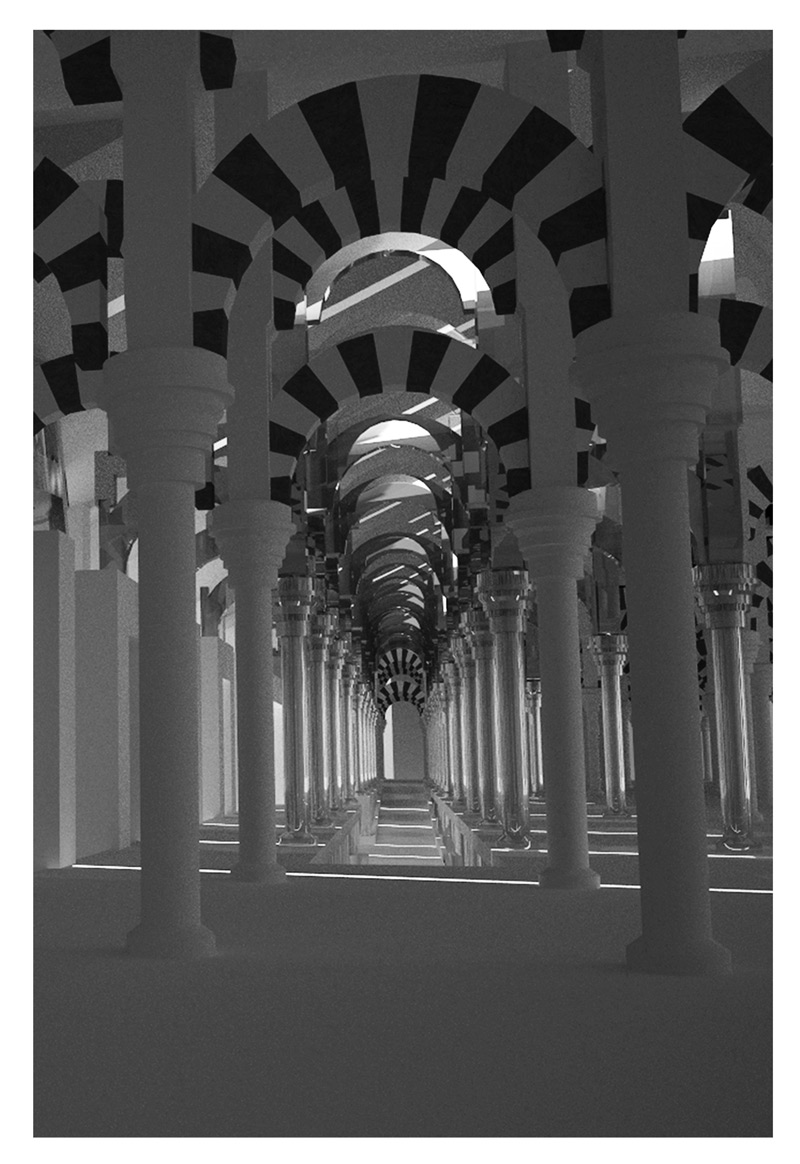

The Mosque of Cordoba was built in 785 by the Prince Abd ar-Rahman I, the founder of the Umayyad Caliphate of Spain. It is located at the south edge of the historic city; there is a Roman bridge that connects the two banks of river Guadalquivir. The mosque creates a mysterious impression of space: there is a forest of colonnades; standing in one position a person would have multiple views of the two storey arcade, making the space seem nearly weightless. The boundless horizon creates a sense of infinity. The space has the desire to draw a person in every direction; the domed areas hold the visitor in one place. The mosque responds to the sky and the cosmos but the sky itself is not visible. One feels the presence of the absence in the mosque.

The most notable feature of the building is its arcaded hypostyle hall, with 856 columns of jasper, onyx, marble and granite, described by Iqbal as ‘countless pillars like rows of palm trees in the oasis of Syria’. The mosque was crafted by Byzantine craftsmen and the material, including complete columns, was taken from existing Roman buildings. The columns branch up to become double horse-shoe arches with alternating coloured stones. The mosque was built on the site of a Roman Temple which was turned into a church that lasted some six hundred years. Abd ur-Rahman I purchased the Church of Saint Vincent, demolished it, and constructed the mosque on the same site.

Over the years, the mosque has been subjected to numerous extensions. It was expanded over a period of two hundred years (785–987) under Muslim rule. The maqsura (screen which encloses the area of the mihrab and minbar) was added during the caliphate of Abd ur-Rahman III (r. 912–961), whose reign marked the height of the Umayyad power. It is the jewel of the mosque. Its purpose was to protect the Caliph from assassination attempts. The Caliph prayed under a sea-shell-shaped domed mihrab, with the cosmos above him in the form of a beautiful cross-vaulted dome. The maqsura was visible from the main entrance of the mosque across the courtyard but was never accessible to the general public. When the mosque was further extended, in 986, on the eastern side, the maqsura became off centre in the basic layout. Even in these extensions, the rhythm of the double horseshoe arches was maintained and the new columns were made to look like the old ones.

What is unique about the mosque is that the mihrab (which indicates the direction of Ka’abah) is due south whereas the actual Qibla is south-east. A possible reason for this could be that Muslims followed the layout of the city which followed a strict Roman grid. They did not disturb the rest of the city’s layout and utilised the foundations of the Church of Saint Vincent. Another hypothesis is that Abdal Rehman I kept the same solar orientation as that of Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, therefore re-enforcing the memory of his homeland. It is difficult to believe that the architects and builders were unaware of the actual direction of the Qibla. What is more likely is that the Cordoba Mosque is situated at different junctures within larger architectural history. As Nuha Khoury, the American architectural historian notes, the mosque’s ‘connections to the past make it the culmination of an older Umayyad tradition, while its particular creative location in al-Andalus makes it the point of inception for a new tradition with different subsequent histories in Spain and North Africa.’

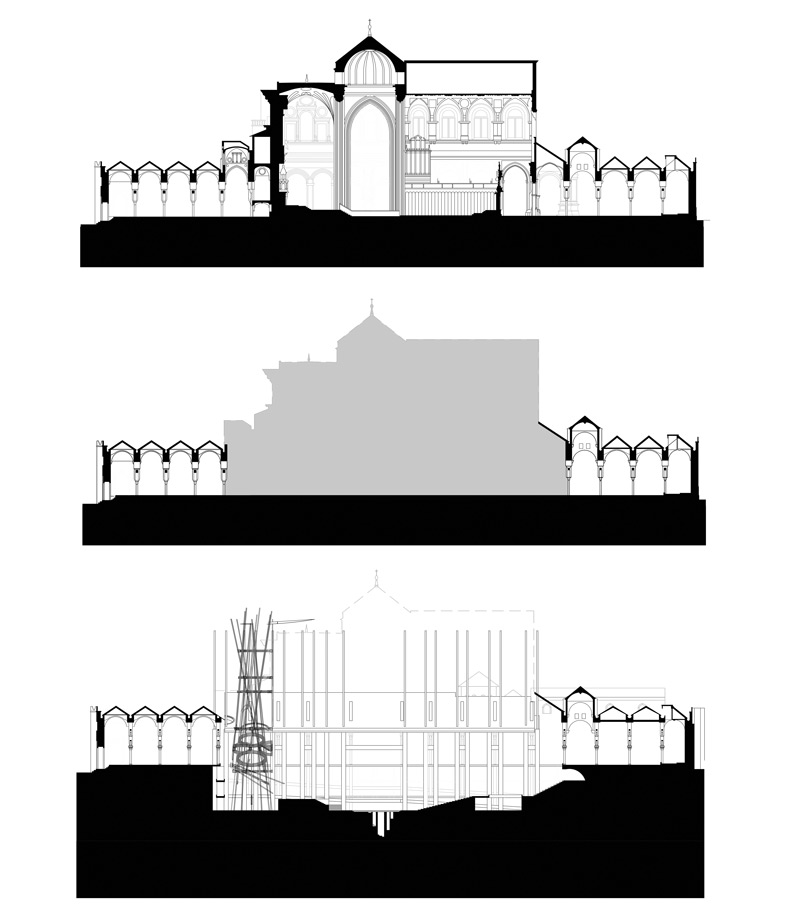

The building remained static until 1236 when, following the conquest of Cordoba by Fernando III of Castile in the Reconquista, it was consecrated as a cathedral. A Villaviciosa Chapel and the Royal Chapel were constructed within the mosque. Further Christian features were added in the fourteenth century, and the minaret of the mosque was converted into the bell tower of the cathedral. Perhaps the most significant alteration came in 1523 when a Renaissance cathedral was built within the expansive structure. The cathedral was dropped right in the middle of the mosque and sits in an east to west direction. It destroys the harmony and delicacy of the double horse-shoe arches. Some sixty-three pillars had to be removed from the mosque so that the cathedral could be made exactly in the centre. The space at the centre of the mosque, which was originally flooded with light, became extremely dark due to the monumental cathedral, which itself has light coming in from its huge windows. The rest of the mosque has several domed areas which pour light into the mosque. It is reported that when Charles V, who supported the building of the cathedral, eventually saw it in 1526, he exclaimed: ‘You have built here what you or anyone might have built anywhere else, but you have destroyed what was unique in the world.’

The ‘Mezquita’, as it is known, now functions as a cathedral and a tourist site. There is Sunday Mass and there are tourists; it is not a mosque anymore. Muslims of Cordoba are not allowed to pray inside the mosque, and a petition to the Pope in 2002 was rejected. Even as a cathedral it functions as a place of worship only on Sundays. Nonetheless, the building still echoes the stories of its origins, displays the burden of its changing roles throughout history, narrates the entire story of the rise and fall of Muslim Spain, announces itself to the world, and has the quality that Iqbal captures in his poem.

Suppose we were to reimagine the Cordoba Mosque as Iqbal saw it. Not as a mosque for Muslims, but as a universal space for all religions, an invitation to the children of Adam to gather in a special place to reflect on the Divine. Not as a cathedral, but free of the Christian attitudes of the Reconquista and the architectural re-assertion of the return of the Christian power. As a place that is an ode to the Heavens and the Earth, and to God and His mercy which is not bound to any religion. What would Cordoba Mosque look like, to use Iqbal’s words, as ‘the reverberation of the symphony of Creation’?

This, then, is a theoretical re-imagining of the Cordoba Mosque, and Andalusia, in the present time.

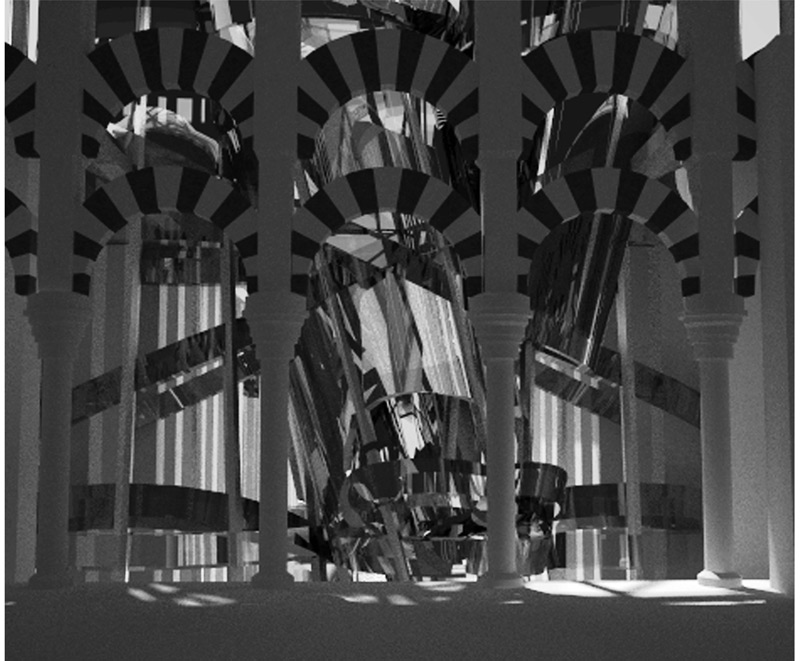

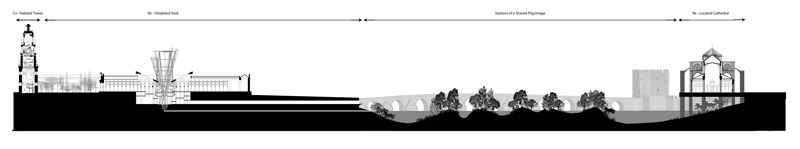

We begin with re-locating the Renaissance cathedral to its metaphorically equal place across the river. The cathedral is moved stone by stone so that it can continue to function but now has a more clear identity of itself, with an opportunity to reflect on itself and focus on the previously occupied mosque across the river. The cathedral leaves a huge void in the mosque. This void, which appears like a missing tooth, is to be developed and inhabited as a centre which is sacred to more than one religion. The mosque will not resume its status of a mosque. It will, instead, offer a space for everyone to gather.

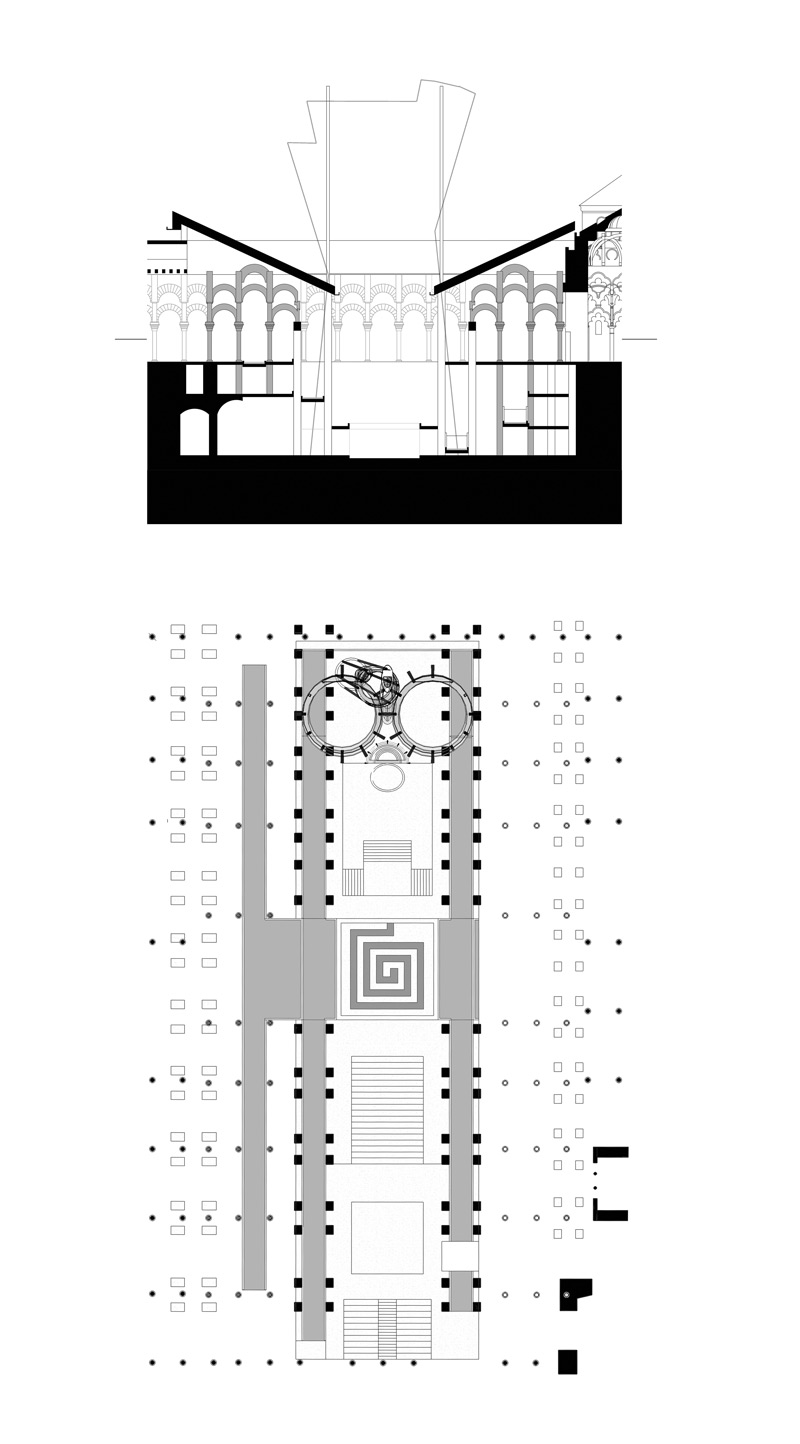

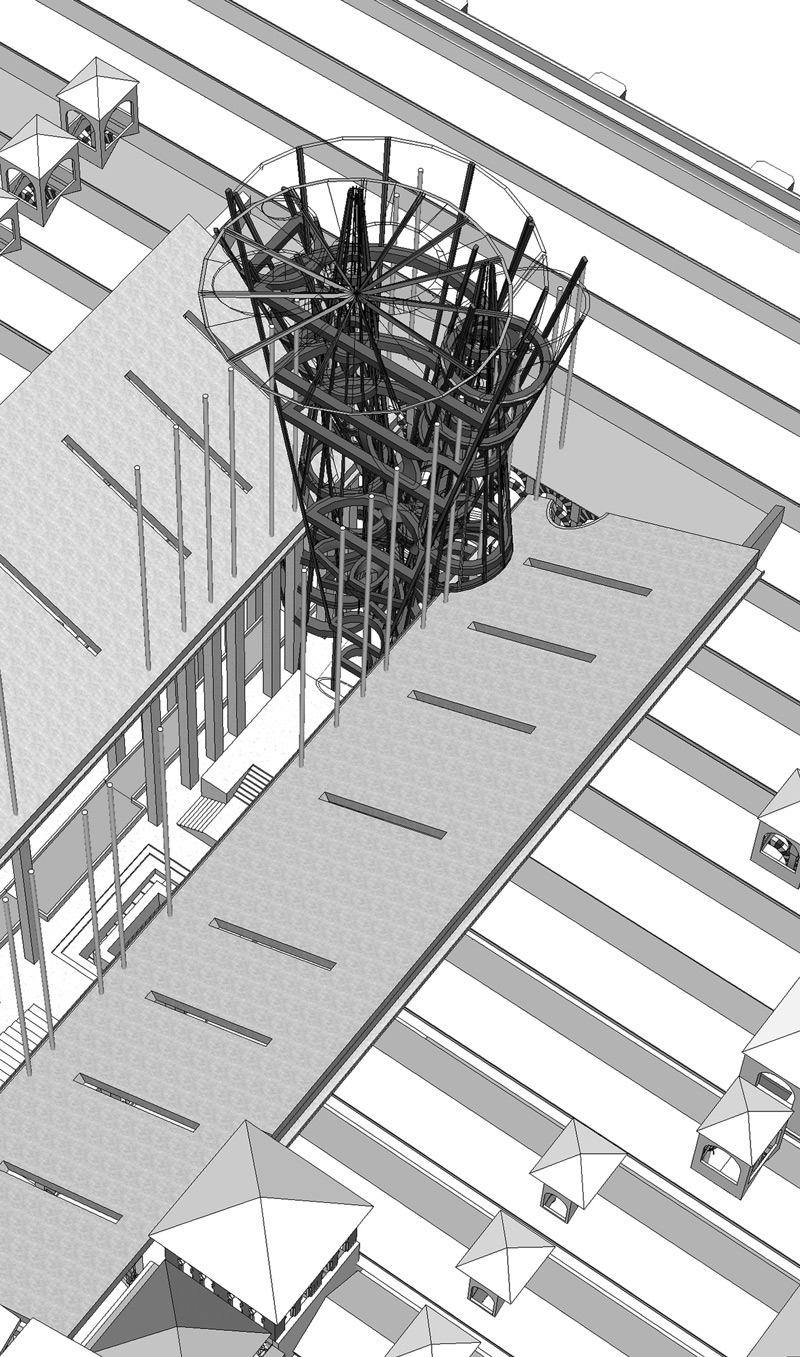

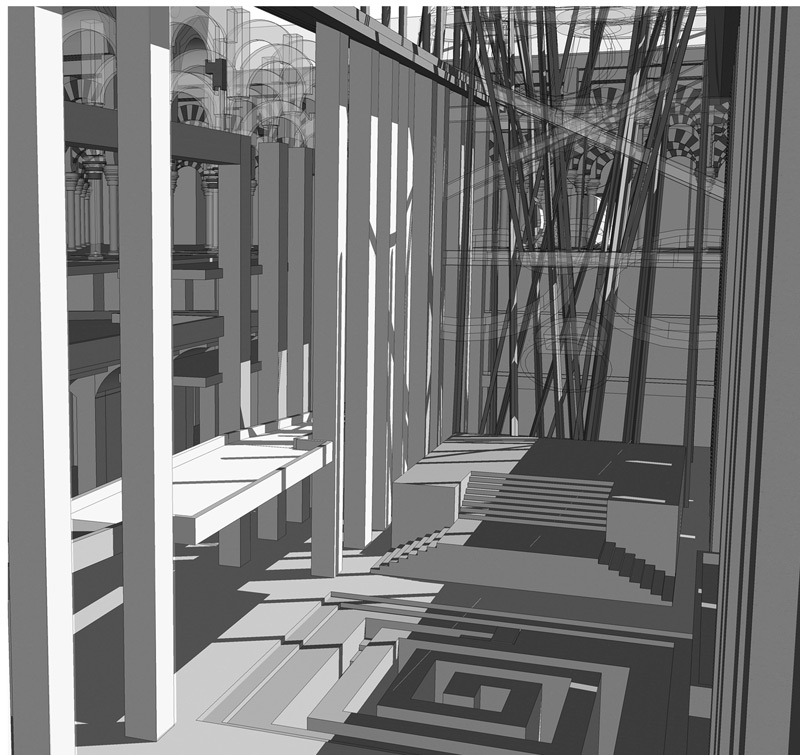

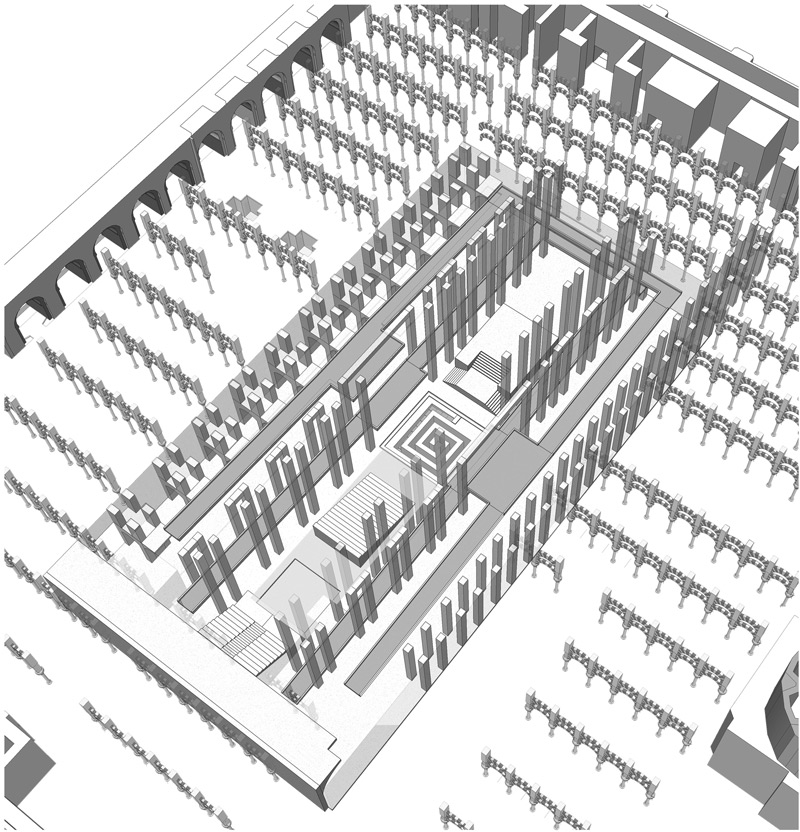

The void left by the cathedral is 138 feet wide and 240 feet long. Some area is to be returned to the mosque; and only 60 feet is used from the 138 feet of width. The void will expand itself underneath the floor which will be utilised and made into library. From the floor of the mosque, the ground will be dug down to about 30 feet so that there is minimum intervention on the ground level, maintaining the infinity created by the colonnade. Amongst the forest of palm trees, this void will be like an oasis, where the wanderers of this world can stop for the shade under the trees to quench their spiritual thirst. It will be transformed into an area for congregation or self-reflection. The void will announce its presence to the sky, but it will be deeply rooted into the nave of the earth. It is like digging back into the foundation of one’s existence to discover and release one’s ego from all desires.

The void is re-inhabited in such a way that the memory of the cathedral’s insertion is imprinted in it. The new intervention respects and acknowledges the absence; it is a carved out courtyard in the vertical axis of the cathedral. Ramps take you down in the carved spaces and invite a circumbulation (tawaf) around the courtyard.

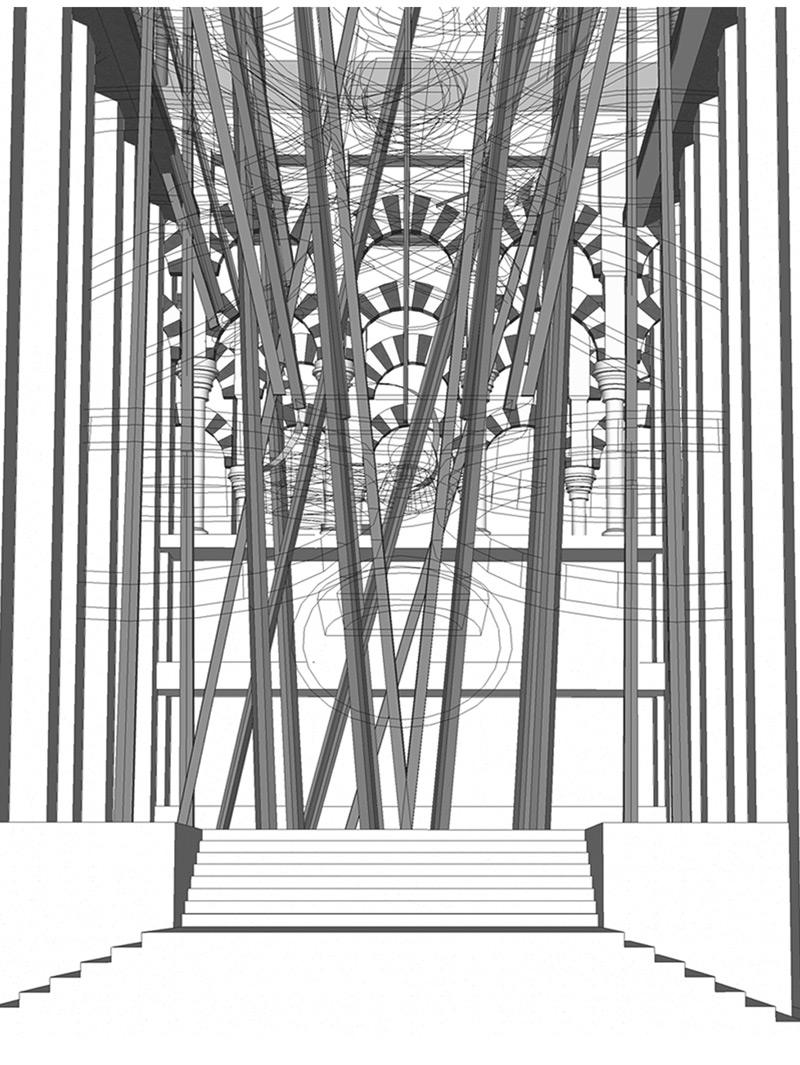

The descent into the memories of the mosque and the cathedral is gradual. The ramp is between a set of glass columns that light the path till the ramp ends. These glass columns fan above you, like a ghost from the past or a faint memory slowly revealing itself. They are rendered weightless by the light which strikes them, illuminating their surroundings and taking this light to where the path ends. During the day, the columns take the light from the punctures right above them on the roof; during the night, they are giving off light. In their second cycle, the ramps are resting between the pilasters that are frozen memories of the cathedral. Thus from the start, the ramps are held by the mosque’s memory and are passed on to that of the cathedral. The ramps spiral from the lowest level of the courtyard moving outwards into and under the open sky.

The void in the axis of the cathedral

The courtyard is a sitting arena of steps facing east. This well of stairs faces the altar and leads to the body of water that reflects the altar and the sky. The body of water is under the pre-existing memory of the dome of the cathedral, symbolically bringing the sky in its place. It is to keep a portion of the sky or God’s mercy in this place; the hands are raised towards the sky receiving the rain water, which is fed to the pool. Water is channelled from the roof to the pool, which in turn gives it back to the life-giving river Guadalquivir. It is as if Cordoba is shedding tears of happiness and providing nectar to the river that has, for centuries, been keeping this place alive. The water flows to the river via an underground channel. The body of water itself has a passageway that can be accessed only when there is no water in the pool. There is another passage that opens up on the bank of the river from the mosque. It is at the south side of the courtyard and at the lowest levels. This new ‘Haram’ or centre pays an ode both to Iqbal and Guadalquivir. The breeze from the river brings fresh songs of Cordoba or narrates stories of the world. The tunnel can be accessed from the river to bring people directly into the re-inhabited void so they can take a journey back upwards to the palm trees of Cordoba.

The re-located cathedral not only leaves a huge void in the centre of the structure but also several punctures or marks in the floor created by its columns and buttresses. The pilasters are in the place where the columns were; around every column, four pilasters are made to demarcate their boundary. The punctures left by the buttresses are approximately 20 feet in length and width. The floor of the Mosque of Cordoba varies because during different extensions new floors were added; the floor holds all the marks of the history of this building. The new floor is dug from the void left by the cathedral; the punctures that have been left by the buttresses are encased. A glass slab is added as a lid for the punctures so that the continuity of the floor is not disrupted; it also adds a visual disparity that serves as a reminder of the history of the building.

The pilasters on the immediate periphery of the courtyard stop at a certain height; steel columns shoot out from them to the original height of the courtyard. They present themselves as the skeleton of a large body: incomplete, barren, just staring or reaching out to the sky. The cathedral on the other side of the river can look back at the place where it once stood, to the height that it was against the gentle horizon of the double horse-shoe arches. This harp-like colonnade shoots out light to the heavens declaring its presence.

Transition towards inhabiting the void

From within the altar

The front view of the altar

The front view of the altar

Courtyard and sea of steps from within the altar

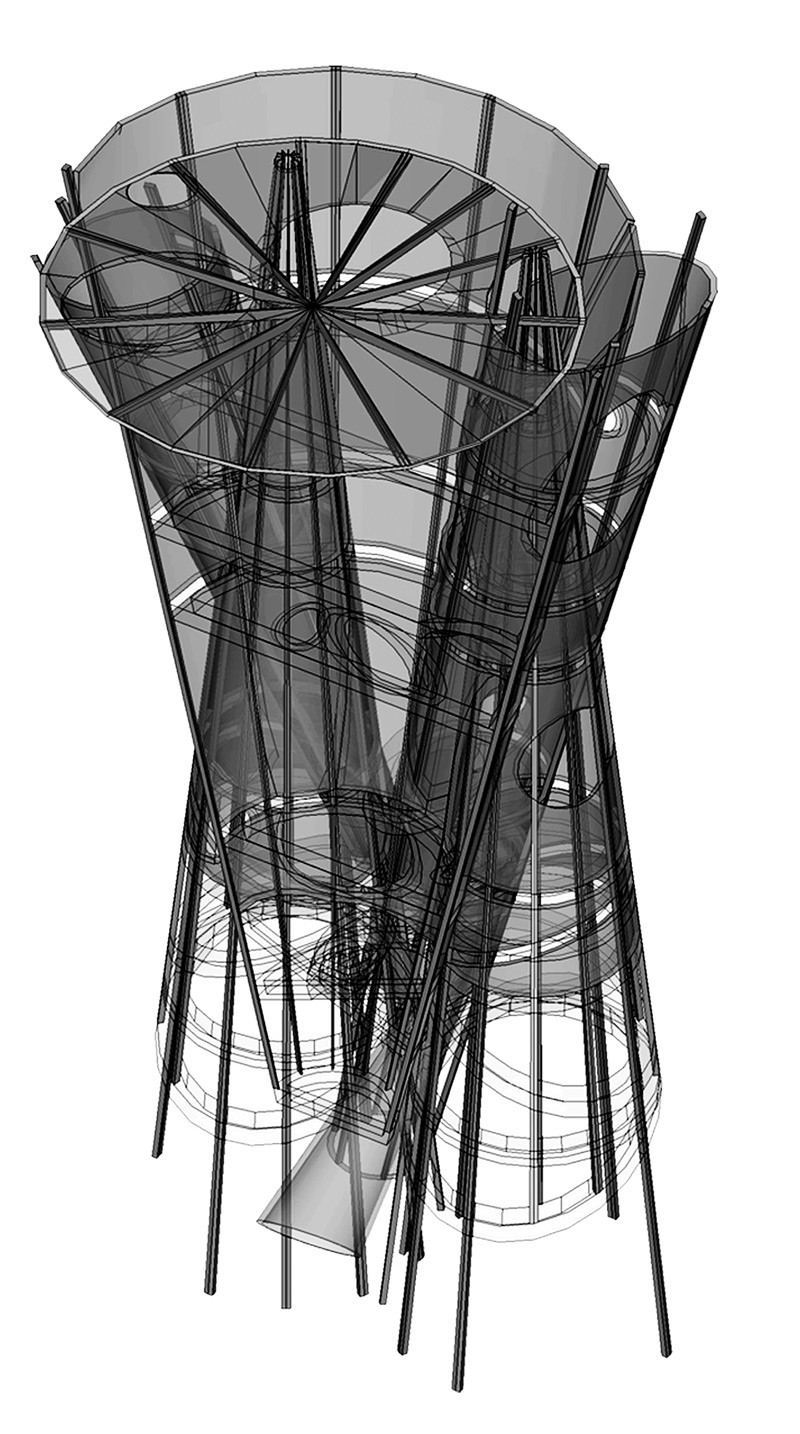

The altar here is paying an ode to the light, to the wind and rain and to the heavens above. It goes up to the height where the dome of the cathedral was located, and is made up of glass cones that are supported by steel rods and rings. On certain special days (solstices and equinoxes), the cones bring in light through its punctures. The altar is like an organ which plays the music of the winds and collects rainwater that is fed to the pool. The cones are hollow and they intersect each other at various junctures. The steel rings demarcate different levels and heights in this building but, more importantly, they employ symbols of different religions.

Rainwater collecting roof and altar

View of the pool and the altar

The ecumenical altar

From beyond the altar

Entering the ramp under the glass arcade

The Circumbulation (Tawaf)

The re-imagined Cordoba Mosque now has:

~ a carved out courtyard framing the base of the vertical axis of the cathedral;

~ a series of pilasters that are in place of the columns of the cathedral to accurately freeze the memory of the cathedral;

~ steel columns that are left open to the sky at the height of the columns of the cathedral;

~ an arcade of glass columns that serve as memories of the mosque columns;

~ ramps that take you down in the carved spaces while performing a tawaf around the courtyard;

~ a library that is under the floor of the mosque, it runs in line with the pilasters;

~ a new altar that employs spiritual signs and religious symbols of all religions and is an ode to light, sound, and water;

~ a pool ‘mandala’ that is in place of the dome of the cathedral, it collects rainwater which is circulated back to the river;

~ an underground tunnel that opens onto the river to let in the breeze and the music of the wind from the river.

But there are still two other things to consider: the minaret and the islands on the Guadalquivir.

The minaret has base dimensions of approximately 40 by 40 feet and has two symmetrical staircases moving to the top with a solid dividing wall between them. With a height of approximately 200 feet, it will serve as a residential place for scholars. These scholars and students will meet and encounter the Cordovan scholars who are present in the tower at all times. The journey upwards in the minarets is divided into four residences each belonging to the legacy of a historic scholar. The base of the minaret and the beginning of the journey is dedicated to ibn Rushd, undoubtedly the most notable son and philosopher of Cordoba. The next apartment is devoted to another son of Cordoba, the Jewish philosopher Maimonides, one of the most prolific and followed scholars of the Torah. The third apartment is for Thomas Aquinas, the Roman Catholic philosopher and theologian who had a long-running argument with ibn Rushd. The final level or stage is given to Iqbal. The minaret represents an architectural allegory in which three scholars of Abrahamic traditions continue their dialogue and discourse, mediated by the universal insights of Iqbal, where all learn to co-habit with each other.

The Guadalquivir, ‘The Life Giving River’, has small islands where a few water mills from the Muslim period of Cordoba have survived, a symbolic reminder of the richness of this place. On these islands, there will be pavilions dedicated to different religions of the world. Each pavilion will show the essence of the religion it is representing in context with nature; together they will provide a space for the common goal of our different spiritual traditions – a symbolic journey from a place of one individual differentiated religion to a place, the Inhabited Void, the Courtyard, that is for all.

The journey that starts from the newly relocated cathedral, through the pavilions in the islands to the philosophers in the minaret and the previously existing mosque, is a celebration of the different appreciations of the Divine. This re-imagined Cordoba Mosque aims to invite everyone to a historically religious site, to link religion to humanism, in pursuit of the shared goals of humanity. It is ‘a vision of some other period of time’, where the wounds of history have been healed with ‘the essence of life’ and where pluralism and humane futures flourish.

The Re-imagined Cordoba Mosque