My work explores the relationship between religion and modernity. Many of my paintings draw conceptually on the social and cultural phenomena associated with the Muslim world, which is why I have named my particular style ‘Islamicate Impressionism.’ I like to focus on visual sensations of Islamic themes while also incorporating elements of magical realism. I believe the magical depictions in my work convey a sense of numinous wonder, evoking the idea that the divine is the everyday and the everyday is the divine. If I have any goal, it is to speak to the truth of the human condition, and perhaps reveal something to the viewer about themself.

My painting ‘The Night Prayer’ adopts the distinctive introspective mood of Edward Hopper’s paintings. I believe the only way I could have shown the particularly individual and private act of tahajjud (the night prayer) was through the vantage point of a window, enabling the viewer to look into this secret world and experience a feeling of intrigue and awe.

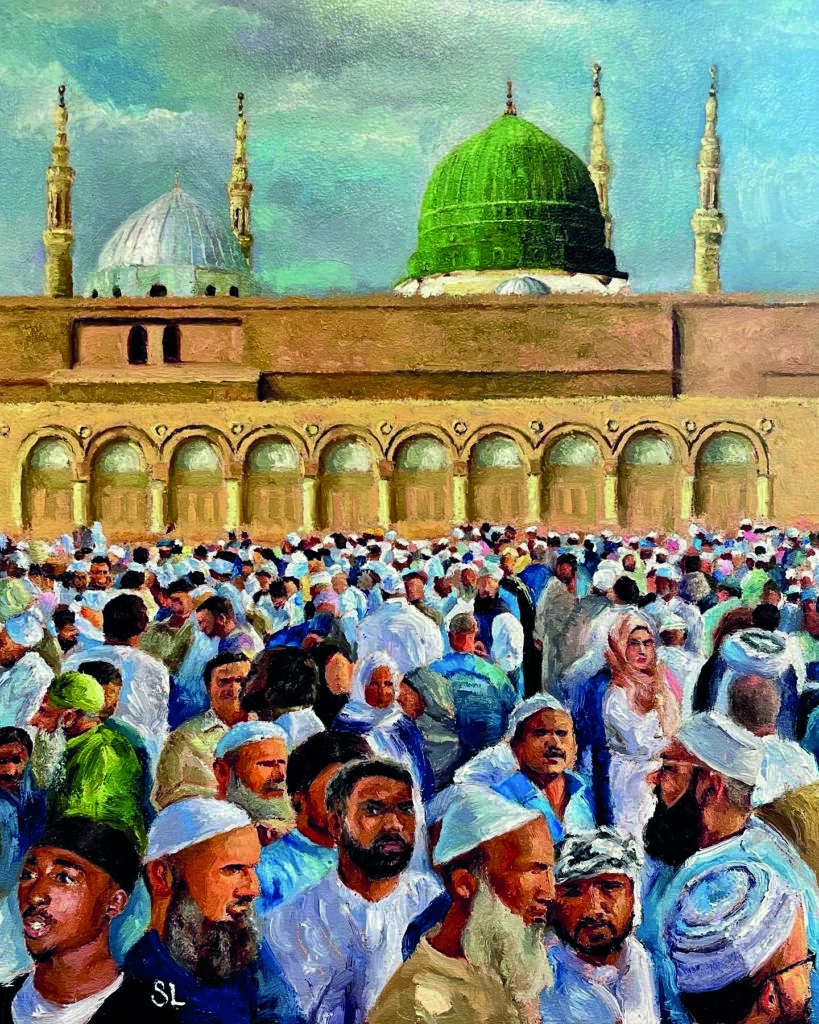

‘Finding Khidr in Medina’ is one of a series of paintings in which I depict the elusive Qur’anic figure Khidr in various locations throughout the Muslim world. The idea invoked is that of the familiar children’s book ‘Where’s Waldo?’ wherein the viewer must go on an epic hunt to find the red stripe wearing Waldo. In ‘Finding Khidr in Medina’, I intentionally painted the composition to feel narrow and perhaps claustrophobic to emphasize the massive and diverse Muslim crowd. Khidr is seen on the bottom left donning green clothing and below him is another enigmatic figure who refuses to die in popular imagination, Tupac Shakur. Thus, this painting emerges as a play on religious and secular experiences of the supernatural.

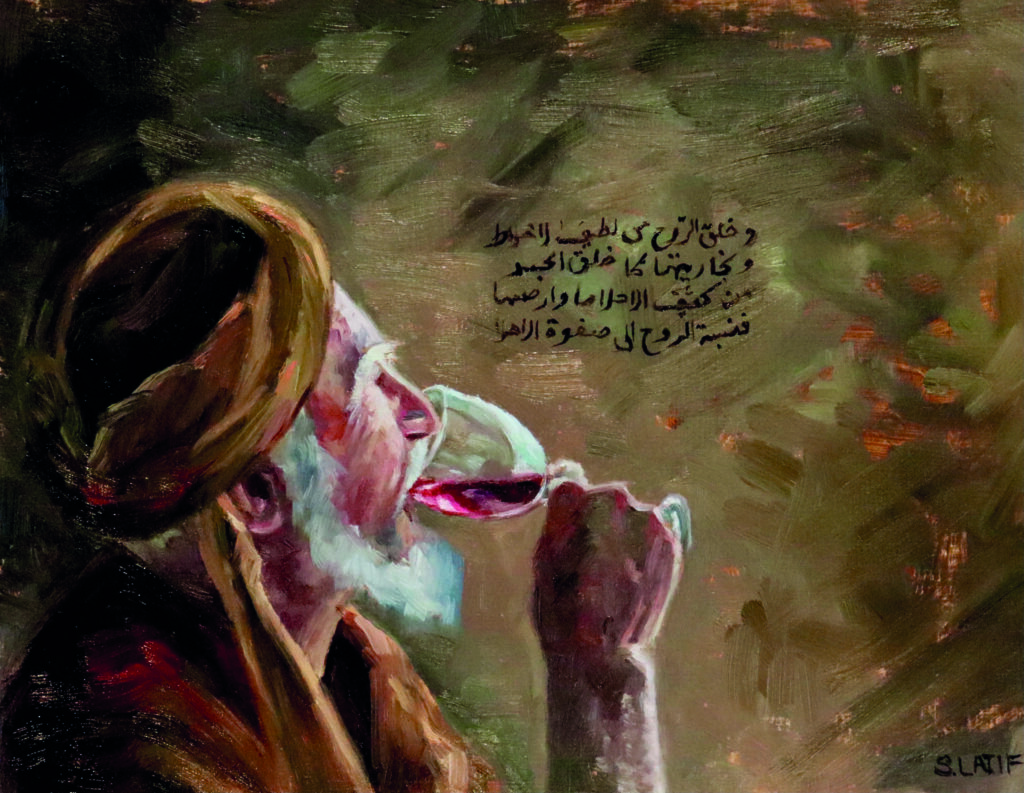

‘Portrait of Avicenna’ (Ibn Sina) goes beyond the parameters of a typical portrait. Here he is depicted conspicuously in the act of drinking wine, a forbidden drink in Islam. This piece may evoke a negative visceral response in many religious adherents, but I believe it forces one to acknowledge a very significant point – that while Islam may be a legal tradition, it is equally non-legal in both spirit and practice. The Arabic written in the backdrop is taken from his book on the heart. I intentionally painted it loose and haphazard to imitate the appearance of manuscript writing. The passage cuts off abruptly mid sentence, giving the impression of a train of thought Avicenna might have had.

‘Call to Prayer’ is inspired by a prominent historical figure in Islam, Bilal ibn Rabah, who was the first muezzin in Islam. The wispy brushstrokes suggest movement and hopefully allow the viewer to experience the emotion associated with the Islamic practice of calling others to prayer.

‘Detachment’ conveys a sense of grandeur emanating not only from the glittering lights and orbs but also from the old man who sits, on the right side of the composition, immersed in dhikr.

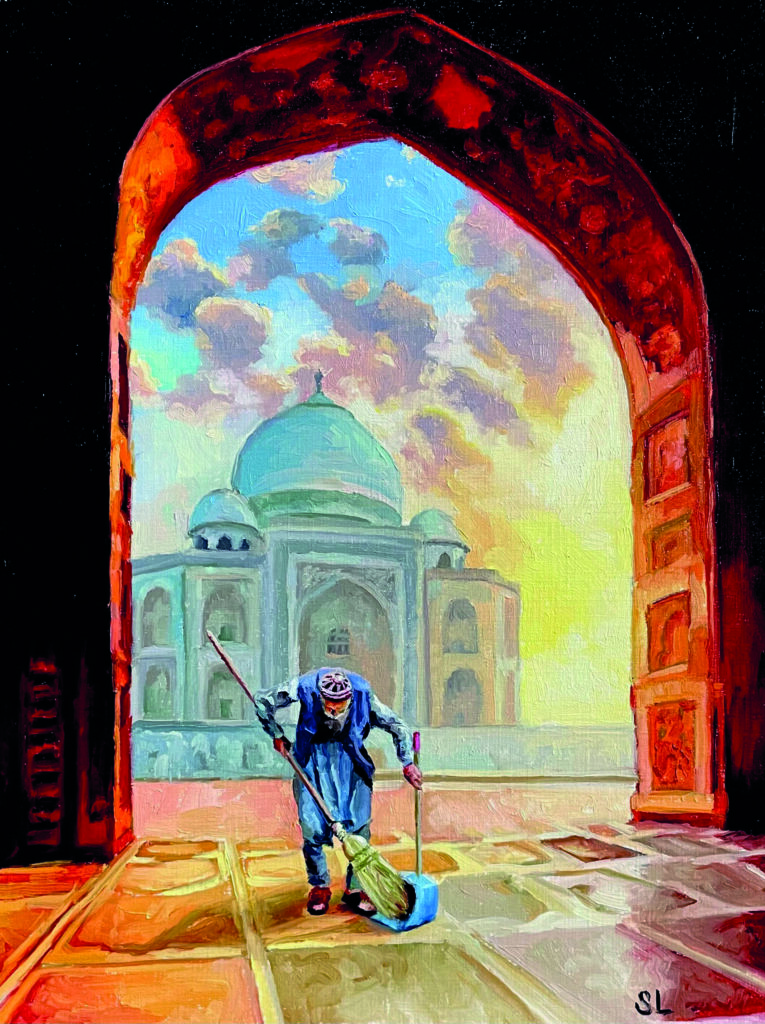

In ‘The Custodian’, I decided to juxtapose the majesty of the Taj Mahal with the quiet and unassuming work of the cleaner. As in ‘Detachment’, the viewer must decide: what or who manifests the splendor and beauty in these paintings?